Category: Segregation

November 3, 2008

by Steve Rawley

Official news that the Young Men’s Academy (YMA) at Jefferson High School will close at the end of this school year is certainly no surprise. But rather than point fingers over obvious mistakes, we should pause and reflect on the lessons to be learned.

Jefferson, Oregon’s only majority black high school, is emblematic of how Portland Public Schools treats its black students. No other high school in Portland offers as few classes as Jefferson — 34 classes currently listed (not counting dance classes), with no music, chemistry, physics, calculus, world languages other than Spanish, or a single A.P. class — and no other high school has experimented with gender segregation or uniforms.

The first lesson we should take away from the failed experiment in not just gender segregation but also “smallness” taken to the extreme, is that size matters. This is a lesson PPS needs to learn system-wide. If we are unwilling or unable to pay for it, we shouldn’t design it into the system.

The young women at the Jefferson Young Women’s Academy (YWA), though faring better than their counterparts at the YMA, are still suffering from unfunded smallness. They are the only high school campus in the district without a staffed library. They also are cut off from the after-school programs at Jefferson, with no transportation provided to and from their satellite campus two miles away.

We should also remember that both YMA and YWA have so far served mostly middle grade students — high school grades have been phased in as students age up — and that the Jefferson cluster does not have a middle school.

By far and away the most important lesson to learn from the failure of Jefferson’s YMA is one of fundamental fairness. Why is the choice of middle grade students in the Jefferson cluster between K-8 or gender-segregated 6-12? Why doesn’t the Jefferson cluster (and Madison, too) have a comprehensive middle school option, like every other cluster in Portland?

Or, to put it more bluntly: Why do we insist on treating black students so much differently (that is, worse) than everybody else?

We should know by now that endless promises, experiments and reconfigurations have only made Jefferson weaker and less desirable to the greater community — declining enrollment figures don’t lie. More of the same may be seen as confirmation of the suspicion heard frequently around the neighborhood: that PPS wants Jefferson (and its black students) to fail.

In the end, what we should take away from this particular failed experiment is that Jefferson students need what all students need: a rich and interesting curriculum, taught by experienced teachers, with opportunity in their neighborhood on par with every other neighborhood in the district.

Portland Public Schools has the facilities, and, more importantly, the neighborhood student populations, to support comprehensive high schools and middle schools in all nine clusters. But the district’s twin experiments in “smallness” and “choice” have led to a system wildly out of balance and shamefully unfair to the students most in need of a comprehensive education.

Perhaps the announcement of YMA’s demise on the day before a historic election augurs a new day, one in which black students in Portland, Ore. have the same kinds of schools in their neighborhoods as white students, and they are no longer subject to ill-conceived, under-funded experiments and second-tier opportunity.

One can only hope.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

16 Comments

October 1, 2008

by Steve Rawley

Talk about playing both sides for the middle.

The newest member of the Portland Public Schools Board of Education is already demonstrating keen political instincts. Even as he speaks of representing minority communities, he’s falling in line with the group think of the board.

“I’m not going to go there and just be an opposition candidate,” says Martín González in a Portland Tribune story by Christian Gaston.

“I think people are looking for magical solutions and I like Kool-Aid, but I don’t think that’s how it works.”

I think González, who has not responded to PPS Equity e-mail challenging him to take bold positions on critical issues, may be talking about us.

Personally, I can’t stand Kool-Aid. And I don’t think having comprehensive secondary schools in our least wealthy neighborhoods and a neighborhood-based enrollment policy is asking for magic. I think it would be equitable, balanced, sustainable public education and investment policy.

If González thinks that’s asking for magic, I think he’s being incredibly cynical.

He falls right in line with the company dogma about transfer and enrollment policy.

González said that the district’s transfer policy isn’t responsible for segregating students: Instead, parents and students are separating themselves.

“The reality is, I think, our society is still segregated,” González said.

Yes, society is segregated, and yes, people do self-segregate. I’ve written about that quite a bit, in fact.

But this doesn’t excuse the district’s policy that encourages more of it. The fact remains that our schools have become dramatically more segregated, both in terms of ethnicity and economics, than the neighborhoods they serve.

This policy González is defending, coupled with the school funding formula, divests over $40 million a year from our least wealthy, least white neighborhoods.

I can understand the perspective of wanting to keep options for poor and minority students, who are disproportionately assigned to schools that the district has not just neglected, but has actively gutted and broken into small schools with dramatically reduced opportunity.

This is why I’ve proposed a transfer policy — predicated on first providing comprehensive secondary schools in every cluster — that allows students to transfer freely, so long as their transfer doesn’t aggravate socio-economic segregation (much like the Black United Front’s 1980 desegregation plan, but keyed on economics instead of race).

This policy would allow disadvantaged students to choose from virtually any school, but keep most students in their neighborhood schools. It would balance our public investment in proportion to where students live, bring equity of opportunity to all students, and it would tend to desegregate schools in all neighborhoods. And best of all, it would cost taxpayers less than the current model with all its built-in inequities.

This isn’t magic, Mr. González, this is sound public policy. If we could do it in 1980, we can do it in 2008.

Platitudes about bringing a new voice to the table and tracking individual student achievement don’t mean much when the policies of Portland Public Schools continue to drain enrollment and public investment from our poorest neighborhoods and deprive the students there of basic opportunity available to students living in the wealthier, whiter parts of Portland.

It’s looking like the school board and their patrons got exactly what they were looking for. A minority male, which changes the balance of the board from 85% female and 71% white to 71% female and 57% white, making the board look more like the 55% white school district they lead.

But best of all, the powers-that-be manage to keep their own white asses covered with a seemingly representative board defending policies which disproportionately hurt poor and minority neighborhoods and students to the benefit of wealthier, whiter ones.

You’ve got to hand it to them; they know exactly what they’re doing. And it sounds an awful lot like class war to me.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

1 Comment

September 21, 2008

by Steve Rawley

Lest the casual reader believe PPS Equity is solely focused on the things Portland Public Schools is doing wrong (we’ve been described as “scathing” by Sarah Mirk at the Merc), we should pause and take note of the things that are on the right track.

In Carole Smith’s September 5 speech (58KB PDF) to the City Club of Portland (reviewed by Peter Campbell here and by Terry Olson on his blog), she highlighted what I see as a significant policy shift from her predescessor. In her prepared remarks, she says

…our high school campuses with the lowest enrollment — the ones usually suggested for closure — each have at least 1,400 high school age students living in their neighborhoods. As a city, we have a choice: We can declare defeat, shut down those campuses and tell 1,400 students they have to take a long bus ride every day to a high school in a more affluent part of town — sacrificing their ability to participate in athletics, after-school programs at those schools that meet families’ needs and are attractive to students.

I’m not ready to give up on those schools and on those neighborhoods.

Hey, I could have written this! In fact, I have, many times.

(The next step is to figure out how to pay for it. I’ve long suggested balancing enrollment through a combination of equalizing opportunities across the district and a neighborhood-based enrollment policy. Carole Smith and her staff haven’t made that next step yet, but unless they have a 50% increase in funding or want to cut programming in wealthier neighborhoods, balancing enrollment is the only way we’re going to get there.)

Finally, we’re hearing talk of “equity of access,” which sounds pretty darned close to the “equity of opportunity” I’ve been calling for.

The significant question about “access” is whether we will continue to have a two-tiered secondary school system — comprehensive middle and high schools for the wealthier half of the city and K8s and “small schools” high schools for the rest — or whether we’re going to work toward eliminating the ability to know the wealth of a neighborhood by the type of school you find there.

Smith is taking the first steps on the path to what I call equity; to that end, her staff, “by the end of this school year, … will define the core educational program to be offered at each of our high school campuses, as well as a plan to fund it within existing resources.”

You have to assume this will be a pretty low bar, as it has been with K8s. (The minimum 6-8 curriculum being defined for the K8 transition is significantly less than what was already available at every middle school in Portland before the K8 conversion.) But we’ve got to guarantee that students are at least able to graduate with the classes available, something that isn’t necessarily possible at some of Portland’s poorest high schools, a problem aggravated by the district’s rigid implementation of the “small schools” model at Madison High School, for example.

Nevertheless, these implementation details, along with a continued focus on assessment, do not detract from the fact that Carole Smith is on the right track in significant, broad stroke ways.

Talking about high schools before talking about facilities. Talking about “equity of access”. Talking about where students live (as opposed to where they’ve transferred to) as a critical element in the design of the high school system.

It’s easy to point to missed opportunities to take immediate action and show a real commitment to equity of opportunity: Madison High, K8s, Libraries, etc. But it seems to me the winds have shifted, and if we actually put some of Carole Smith’s words into bold action, we’re going to see a turn-around from the laissez-faire, two-tiered, self-segregated “system” of education we currently have.

Then it just becomes a question of urgency. Every year we wait, we lose another class of students.

It wouldn’t hurt if the school board put a little more wind at Carole Smith’s back in this regard.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

7 Comments

September 14, 2008

by Steve Rawley

As the newest member of the Portland Public Schools board of education, I would like to extend a cordial welcome to Martín González in the form of a challenge on a number of critical issues, in no particular order.

- High schools: advocate for comprehensive high schools in every neighborhood, with the schools offering the best variety of courses and the most qualified teachers sited in the poorest neighborhoods. This policy, the inverse of the current high school system, would rebuild enrollment and public investment where it is most needed. “Small schools,” as currently implemented, may be offered as a special focus, but should never be substituted for comprehensive schools.

- Facilities: advocate for building new facilities based on where students live, not where they’ve transferred, a policy of investing in proportion to local student population and encouraging families to stay in (or return to) their neighborhood schools.

- K8 transition: advocate for a comprehensive middle school option in every neighborhood. K8 schools may be the best option for some students, but they offer dramatically less educational opportunity and are more segregated than middle schools. (Before this transition, every middle school student in PPS had access to a staffed library. Now many do not.) PPS middle grade students assigned to K8 schools are significantly more likely to be non-white and poor than those assigned to middle schools. If any student has a middle school option in their neighborhood, all students should.

- No Child Left Behind: bring a resolution to the board calling for the repeal of the punitive aspects of this law that unfairly target poor and minority students, and introduce policy directing district administration to de-emphasize assessment in favor of a more rounded, whole-child educational focus.

- Student transfer and school funding policies: advocate for a school funding policy that would reinvest in schools that have been gutted by out-transfers as a way to bring enrollment back. Introduce policy that would shift our public investment back to where families live, and guarantee a minimum core curriculum (including the arts) in every neighborhood school. If you really want to be bold, propose policy that would limit neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers to those that would not adversely impact socio-economic segregation. That is, students who qualify for free or reduced lunch could basically transfer anywhere, but other students could only transfer into Title I schools, much like the transfer policy in place during the 1980 desegregation plan (but keying on income instead of race).

- Charter schools: come out strongly for neighborhood schools. Learn from charter school applications what’s missing in our neighborhood schools, and advocate for policy to provide these things in neighborhood schools. The most recent PPS charter school proposal suggests nothing we shouldn’t already be doing in every neighborhood school.

González has a unique opportunity to “audition” for the seat that he will have to win by popular vote in May. How he performs on each of the above issues will signal where he stands with those of us who want school system based on equity of opportunity, where the wealth of a neighborhood does not correspond to the wealth of offerings in its schools.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

2 Comments

September 14, 2008

by Steve Rawley

The latest charter school to rear its head in north or northeast Portland represents a clear challenge to Portland Public Schools, a challenge they have so far refused to meet.

Nothing proposed by the Emerald Charter’s organizers is anything we shouldn’t get in our neighborhood public schools: community building, respect, excellence, and diversity. (In fact, the charter schools movement by its very nature goes against community building and diversity and will likely never come close to neighborhood schools in those areas.)

But you don’t have to read very far into Emerald’s Web page to see a perfectly reasonable rationale to break away from PPS. “Are we teaching students how to learn,” ask the organizers, “or are we giving them a series of rote exercises to get them through the next series of tests?”

This is exactly the question that many activists have asked, and some have pointed out that the PPS obsession with assessment predates No Child Left Behind. The more recent obsession with the “achievement gap” has ensured that Portland schools, especially in neighborhoods that are not predominately white and middle class, have increasingly focused on preparation for assessment to the detriment of “enrichment” (art, music, P.E., world languages, recess etc.).

Whether or not this focus does anything to help bridge the “achievement gap” (some schools that have done away with test prep entirely have actually shown better progress), it is clearly driving white, middle class families away from their inner north and northeast neighborhood schools. The resulting self-segregation reflects the contemporary sociological phenomenon of people tending to associate almost entirely with people who think, act, and look like them.

I cannot criticize anybody for doing what they think is best for their children — that’s their job as a parent. I want nothing to do with name calling and angry debates about personal choices, but people who believe their charter somehow won’t be part of a regressive social movement — with race as a significant aspect — are sorely misguided and misinformed.

Charter schools are, in fact, a regressive social movement; their promise is illusory. I wrote about this in a Portland Tribune op-ed last winter. Nothing has changed since then.

There is a notion that since PPS has historically failed poor and minority students, these communities should be allowed to take their state education money and take care of themselves. It’s hard to argue with the success of the Self Enhancement Academy’s work with its almost entirely African-American student body (five of 137 students were non-black last year).

But the fact that more black students are enrolled in Self Enhancement than in the other six PPS charter schools combined tells the story of “diversity” in charter schools. Every recent charter school application has promised diversity; none have delivered. Portland’s charter schools represent another form of the self-segregation encouraged by the district’s student transfer policy.

Postmodern identity politics is no way to run a public school system, and it is certainly not what we should be teaching our children.

The PPS board of education must be made to understand this latest charter school as a shot across the bow of the district’s assessment obsession. At least three of the current board (Adkins, Williams and Wynde) appear opposed to new charter schools on principle. But Carole Smith’s administration seems entirely sold on the current edu-speak lingo that says we need to focus on “closing the achievement gap” and “equity of outcomes,” goals that have put us into the vicious cycle of stripping “enrichment” as we chase “achievement” as measured by standardized tests.

If school board members want to head off this kind of challenge to the common schools model, they need to create policy that pulls the district away from assessment mania and creates neighborhood schools that consciously focus on the simple things the Emerald Charter’s organizers talk about.

There is nothing revolutionary in turning away from educational trends that have been disastrous for poor and minority children, not to mention the middle class children who would be their classmates. The PPS board needs to quit waffling on this. They should proclaim NCLB a bad law, and declare assessment obsession a detriment to whole-child learning and a significant contributor to inequity and segregation. It makes no sense to continue creating fertile ground for more charter schools that will drain more families from neighborhood schools.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

20 Comments

August 10, 2008

by Terry Olson

I think it can be safely said that the goal of PPS Equity is to ensure that all public school students in Portland, regardless of skin color or family background, have access to decent schools in (or near) their own neighborhoods. They shouldn’t have to travel halfway across the city to find schools with a competent principal, good teachers, a library, and programs that include music, art, foreign languages and physical education. (Note: PPS Equity actually has a mission statement now, which pretty well matches this description. –Ed.)

Unfortunately that goal will never be realized as long as the district keeps judging (and demonizing) schools by the relative wealth of their students (that’s essentially what standardized test scores reveal); and if it refuses to shut down the conveyor belt that empties poor neighborhoods of students and money.

The conveyor belt is the district’s transfer policy, a policy that both enables and encourages school choice. Portland Public Schools leadership, including the school board, seems disinclined to address the crisis of school inequity caused in large part by the transfer policy. And I fear that won’t change with the probable appointment of new board member Martin Gonzales. From what I know of Martin, he’s pro-school choice.

I’ve been the recipient lately of some troubling comments that choice and transfer benefit poor and minority students, and that to deny them the right to choose is to “trap” them in “failing” schools. That’s precisely the stance of the pro-privatization and pro-school choice Cascade Policy Institute and it’s co-conspirator, the Black Alliance for Educational Options.

School choice, in short, has become a civil right.

The reality in Portland reveals how wrong-headed that belief is. Choice leaves behind — or traps, if you will — the poorest and darkest skinned students in schools that struggle to provide barely adequate educational programs.

The Flynn-Blackmer audit (232 KB PDF), Steve Rawley’s research (261 KB PDF), and PPS staff’s graphic presentation to a school board subcommittee last fall all show how choice and transfer further segregate Portland’s students by race and by class.

For a public school district to tolerate, and even encourage, policies that create such race and class-based disparities is intolerable.

So what can be done?

First the school board has to acknowledge that many, perhaps half, of Portland’s lower income schools are in crisis. Confronting that crisis requires bold funding measures to restore programs to low income schools comparable to those found in wealthier schools.

Secondly, (and this is my personal opinion), the board must short circuit the school transfer conveyor belt. We already are witnessing limitations on transfers for the simple reason that students who want out of their “failing” schools have no place to go. In time, the transfer system will grind to a halt on its own, choked to death by congestion. How many Lincolns or Ainsworths, after all, are left to accept desperate students?

Lastly, the district and the board should stop using No Child Left Behind as an excuse for inaction. I’ve suggested that the district thumb its nose at the new federal Title I* mandates. It should take a stand, a dramatic stand, hoping that a new Congress will either refuse to reauthorize NCLB or revamp it to help, not punish, struggling low income schools.

School choice (again, my personal opinion, not the official position of PPS Equity) is a pie-in-the-sky fantasy. It’s a self-defeating approach to school improvement, one that will ultimately lead to the total privatization of our once proud public educational system. It already has gone a long way toward undermining neighborhood schools. Choice is at the heart of No Child Left Behind, a law that pushes charter schools and punishes low income schools with mandated transfer options.

It’s time to end them both.

* (I figure that opting out of Title I would cost the district 8% of it total budget.)

Terry Olson passed away in October, 2009. He was a retired teacher and a neighborhood schools activist. His blog, OlsonOnline, was a seminal space for the discussion of educational equity in Portland.

13 Comments

August 6, 2008

by Steve Rawley

The Sentinel reports today that the US Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has opened an investigation of Portland Public Schools based on the complaint of Marta Guembes on behalf of limited-English proficiency (LEP) students at Madison, Marshall and Roosevelt.

In a letter to superintendent Carole Smith dated July 15, 2008, the OCR notifies PPS that it is under investigation for violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, specifically for:

- failing to provide LEP students the services necessary to ensure an equal opportunity to participate effectively in the district’s educational program; and

- failing to provide information in an effective manner to the parents of LEP students concerning their children and school programs and activities.

The choice of schools is illustrative of the segregation that reflects the concentration of immigrant populations in schools that form an outer ring in Portland, exacerbated by high out-transfer rates of white, middle class students to schools in whiter, more affluent neighborhoods.

Marshall, in outer southeast, is 22.9% English language learners (ELL), Roosevelt, in north, is 19.1% ELL, and Madison, in outer northeast, is 14% ELL.

Of the other high schools in Portland, only Franklin has more than 10% ELL (10.2%). Jefferson is 8.6%, Benson 5%, Cleveland 4.1%, Wilson 3.4% and Lincoln 1.2%.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

3 Comments

July 16, 2008

by Steve Rawley

The biggest problem with Carole Smith’s “equity administration” is that no leaders in Portland Public Schools are willing to define a base level of curriculum that every child is entitled to, in every neighborhood school.

This is fundamental to working toward equity.

Without this definition, district leaders are free to talk about equity at every opportunity, but can avoid actually taking meaningful steps toward it.

Equity immediately achievable

This much is true: it is immediately possible, with available funding, to offer equal educational opportunity in every neighborhood school, simply by having kids go to school in their neighborhoods.

I’m not talking about cookie cutter schools, or replicating programs like Benson in every neighborhood. I’m talking about every child guaranteed an education with a common K-12 core curriculum, ideally including library, music, art, science, math, language arts, social studies, health and world languages.

This is what our neighbors in Beaverton get, through a combination of an extremely strict transfer policy, relatively large schools, and a clearly defined core curriculum. You can walk into any neighborhood school in Beaverton and find a common level of what PPS calls “enrichment,” regardless of the income level or ethnic makeup of the neighborhood.

Contrast this with Portland, where schools vary dramatically, and race, income and address are the best predictors of the kind of opportunity available to students.

We don’t need 2000-student high schools to do this, but we clearly can’t do it in 600-student high schools with the existing funding formula.

While the size of Beaverton’s schools may rankle many idealists, I personally would rather have a large institution with smaller and more classes than a smaller institution with larger and fewer classes.

Details can vary, of course. But we must have a centrally-defined core curriculum, or we will never see equity. And we need to return to neighborhood-based enrollment to achieve the economy of scale necessary to pay for this.

Baby steps not working

Ask yourself how much equity we’ve gotten since it was declared the “over-arching” goal of current leadership.

So far, the “baby steps” approach has seen continued enrollment drains and FTE cuts in our poorest schools. There has been neither talk nor action on addressing the enrollment drain, i.e. the transfer policy, or the FTE cuts, i.e. the staffing formula.

Our schools continue to become more segregated, with dramatic differences in curriculum between white, middle class schools and poor and minority schools. These differences become especially stark and intolerable at the secondary level.

Poor and minority middle school students are disproportionately likely to be assigned to PK8 schools, where they are more likely to be deprived of libraries (nearly a third of PK8 schools completely lack library staff) and the kind of curriculum breadth available at comprehensive middle schools, where white, middle class students are more likely to be assigned (and which all have at least some library staff).

This pattern continues in high school, with white, middle class students generally assigned to comprehensive schools with broad curriculum, and poor and minority students overwhelmingly assigned to “small schools” with far less opportunity.

District leaders refuse action for fear of alienating middle class

By taking the transfer policy off the table, leaders seem to have convinced themselves that we can’t afford a common curriculum. To speak of it would be to acknowledge that we indeed have the means to solve the equity crisis, but won’t, for fear harming the neighborhoods that benefit when district policy siphons enrollment, funding and opportunity out of North, Northeast and outer Southeast Portland.

This unspoken fear — that we will alienate a few hundred middle class white families if we take bold steps toward equity — is unfounded and ironic, especially considering the number of families I personally know who have pulled their children from PPS, or plan to for secondary school, precisely because they cannot receive a fair shake in their neighborhood schools.

It is unethical to maintain current policy based on this fear. How can we deprive at least half of our students of opportunity to benefit the other half?

I don’t believe there is anybody currently on the school board who has both the conviction and the courage — it takes both — to come to the table with policy proposals that will even begin to address this issue.

Terry Olson is right; we need to start working toward electing three strong leaders to school board zones four, five and six in May. We need bold leadership in times of crisis, and we’re not getting it from the current crop of school board directors.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

16 Comments

July 1, 2008

by Steve Rawley

Sixty-one years after Mendez v. Westminster, 54 years after Brown v. Board of Education, 51 years after the Little Rock 9, 48 years after Ruby Bridges, 45 years after George Wallace caved to the national guard at the University of Alabama, 28 years after Ron Herndon stood on the school board desk and demanded equal opportunity for Portland’s black school children, and two years after city and county auditors demanded justification for effectively segregationist enrollment policies, Portland Public Schools have become more segregated than the neighborhoods they serve.

The school board refuses to answer the auditors, and shows no intention of changing the policies that have created the situation.

The segregation (or “racial isolation,” as the district calls it) would not be so objectionable, if it weren’t for the fact that schools in predominantly white, middle class neighborhoods have dramatically better offerings than the rest of Portland.

The desegregation plan hatched by Herndon’s Black United Front and pushed through by then-school board members Steve Buel, Herb Cawthorne and Wally Priestley in 1980 did away with forced busing of black children out of their neighborhoods, added staff to predominantly black schools, and created middle schools out of K-8 schools to better integrate students within their neighborhoods.

For several years, things clearly got better for non-white, non-middle class students in PPS. Then the nation-wide gang crisis hit Portland in 1986, with white supremacist, Asian and black gangs wreaking havoc and contributing to a wave of white flight from Portland’s black neighborhoods and schools. This was followed by the draconian budget cuts of Oregon’s Measure 5 in 1990, which ended the extra staffing brought by the 1980 plan.

Under inconsistent funding and unstable central leadership throughout the 1990s, central control over curricular offerings devolved to the schools, and the gravity of a self-reinforcing pattern of out-transfers and program cuts became virtually insurmountable.

The devolution of curriculum was formalized under the leadership of Vicki Phillips in the early 2000s. Her administration pushed market-based reforms and “school choice” as a salve for the “achievement gap,” and used corporate grants to extend reconfiguration of high schools in poor neighborhoods into “small schools” which severely limited educational opportunities available to Portland’s poorest high school students.

(Small school conversions were tentatively under way at Marshall and Roosevelt when Phillips took office, but didn’t become the de facto model for non-white, non-middle class schools until Phillips pushed it through at Jefferson, against community wishes, and finally at Madison, casting aside the designs of veteran educators who had initiated the concept.)

A bond measure whose revenue was intended to restore music education to the core curriculum was instead frittered away in the form of discretionary grants to schools. Principals in poorer neighborhoods continued to put teaching resources into literacy and numeracy at the expense of art and music, while schools in white, middle class neighborhoods continued to offer a broad range of educational opportunity.

The Phillips administration also began to dismantle middle schools in poor neighborhoods, including, notably, Harriet Tubman Middle School, which was created under the 1980 desegregation plan. This move back to the K-8 model added significantly to the resegregation of middle school students.

It also turns out that middle schoolers in K-8 schools, who are disproportionately non-white and poor, get fewer educational opportunities at greater cost to the district. Predominantly white, middle class neighborhoods have, by and large, been allowed to stick with the comprehensive middle school model, which allows them to offer a much broader range of electives, arts and core curriculum at no additional cost.

So in 28 years, we have moved from a reasonable semblance of equal opportunity, with schools’ demographics reflecting their neighborhoods’, to a demonstrably “separate and unequal” system, with schools more segregated than their neighborhoods.

Current policy makers like to blame Measure 5 and the federal No Child Left Behind Act for the wildly distorted educational opportunities in the district, and they generally refuse to examine district policy in the context of the advances in equity that were realized 28 years ago.

PPS has managed to maintain pretty good schools in white, middle class neighborhoods through years of stark budget cuts, but they have left poor and minority children fighting over crumbs in the rest of Portland. Even as the steady march of gentrification makes our neighborhoods more integrated, our schools are more segregated than they were in the early 1980s.

When today’s school board speaks of “school choice,” the “achievement gap” or “equity,” they appear to speak in a historical vacuum. I hope to remind everybody of the context of PPS’s policies, and the continuum of institutional racism they are a part of. These policies are indeed racist in effect, no matter how they are rationalized or how they were originally intended.

And no matter how much they complain that their hands are tied, or how much they claim to be making progress by “baby steps,” the school board has total control over district policy. They could start rectifying this immediately if they wanted to. Yes, it’s hard — ask Steve Buel or Herb Cawthorne about their late-night sessions trying to push the 1980 desegregation plan through — but it can be done.

I know there are school board members who care deeply about equal opportunity. They may even be in the majority, depending on who is appointed to replace Dan Ryan.

But nobody on today’s school board has demonstrated the political courage or vision necessary to stand up for all children in Portland Public Schools.

With baby steps, we will never get where we need to go. Bold, visionary action is required.

Edited January, 2016: For more background on Ron Herndon and the Black United Front, watch OPB’s Oregon Experience Episode “Portland Civil Rights: Lift Ev’ry Voice.”

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

34 Comments

February 8, 2008

by Steve Rawley

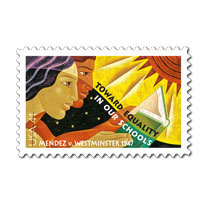

NSA founding member and PPS Equity contributor Anne Trudeau sends along a note that she saw this stamp at the post office the other day.

The stamp commemorates the 60th anniversary of the landmark 1947 Mendez v. Westminister School District federal court decision, which held that Orange County schools could not segregate Mexican and Mexican American students into special “Mexican” schools.

Earl Warren, then governor of California, signed a law later that year that eliminated segregation of Asian school children in California schools, then went on to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and write the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

The US Postal service issued the stamp in September of 2007.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

1 Comment

Next Entries »