Category: Transfer Policy

September 7, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Oregon Public Broadcasting’s morning talk show Think out loud is covering school equity on the first day of school (Tuesday, September 8), with a focus on the PPS high school redesign. Guests include yours truly, Jefferson principal Cynthia Harris, and John Wilhelmi, who headed up the high school redesign effort for PPS.

The show airs live 9-10 a.m. and is rebroadcast at 9 p.m. the same day. You can also listen online or download podcasts after the show has been broadcast.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

Comments Off on On the air

July 21, 2009

by Steve Rawley

A member of the Oregon Assembly for Black Affairs (OABA) e-mail list asks this very pertinent question:

Can anyone…help me understand the benefits to Black students to be required to attend a high school with an impoverished academic program compared to other Portland public high schools just because the Black students live in the neighborhood of an academically impoverished school?

This question is in response to Carole Smith’s announcement of a high school system redesign that would balance high school enrollment by eliminating the ability to transfer between neighborhood schools (choice would be preserved in the form of district-wide magnets, alternative schools, and charters).

The ideal, of course, is that all neighborhood high schools would have equitable offerings, so nobody would be “trapped” in a sub-par school.

But there is a significant lack of trust in the community, which Smith acknowledges. In her press conference announcing the redesign last month, she endorsed the restriction of transfers “with this caveat: We cannot eliminate those transfers until we can assure students that the school serving their neighborhood indeed does measure up to our model of a community school — with consistent and strong courses, advanced classes and support for all.”

In my minority report on high school system redesign, I proposed exceptions to the “no transfers” rule for transfers that don’t worsen socio-economic segregation.

“In other words,” I wrote, “a student who qualifies for free or reduced lunch could be allowed to transfer to a non-Title I school, and a student who doesn’t qualify for free or reduced lunch could be able to transfer to a Title I school. This is a form of voluntary desegregation that is allowable under recent Supreme Court rulings, since it is not based on race.”

I’m not sure if this is the kind of caveat Carole Smith is talking about, but I believe the district has proven it cannot rely on the trust of poor and minority communities who have been disproportionately impacted by district policy. In addition to increasing integration in our schools, this would provide a critical “escape valve” for minority communities while the district demonstrates its good faith.

While our current system ostensibly offers all students the opportunity to enter the lottery to get into a comprehensive high school, only students in predominately white, middle class neighborhoods are guaranteed access to a comprehensive secondary education.

The propposed high school redesign is definitive step toward closing this glaring opportunity gap (even if the achievement gap persists).

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

6 Comments

June 24, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Carole Smith presents her high school plan on the steps of Benson High

In her boldest policy proposal since taking the reigns of Portland Public Schools, Carole Smith has endorsed a high school system design that would guarantee every student a spot in a truly comprehensive high school, eliminate the ability to transfer from one neighborhood school to another, and preserve all existing high school campuses as either comprehensive neighborhood schools or magnets.

This model, described by Smith at a press conference on the steps of Benson High School this morning as “simple, elegant, equitable — and a lot of work,” builds on the success of our existing comprehensive high schools, but will likely preserve small schools as magnet options.

Smith acknowledged the difficulty of gaining community support for such sweeping changes. “I know that many Portlanders — justifiably — don’t really trust the school district to make significant changes. They’ve seen faulty implementation and have felt burned by rushed decision-making — whether your experience is with Jefferson High School or the K-8 reconfigurations,” she said.

Documents describing the design in fuller detail were posted on the PPS Web site this morning. More details will be presented in September.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

5 Comments

June 23, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Superintendent Carole Smith will announce her recommendation for the high school system redesign tomorrow, 10:30 am on the steps of Benson High School. Advance reports indicate the chosen design will be most similar to the “strong neighborhood schools” model (which was the strongest of the three proposed models), with school choice limited to district-wide magnet schools, charters, and alternative schools.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

Comments Off on High school design press conference

June 15, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Note: The Superintendent’s Advisory Committee on Enrollment and Transfer (SACET) was asked to study and report on the high school system redesign. The SACET report (67 KB PDF) was issued in May, with the full support of 12 of 14 members of the committee. One member supported the report with some questions, and one member, your humble editor, could not support the report.

There was no official mechanism within the committee to issue a minority report, so this report is an ad hoc response to the shortcomings of the SACET report. As a member of that committee, I bear a share of responsibility for these shortcomings, so this report is not intended as a personal attack on any of my committee colleagues who spent a great deal of time and energy on a report that reflects much that I agree with. Rather, it seeks to cover areas that SACET did not cover, and amplify their call for “a plan that has neighborhood schools as its foundation.”

This report refers to the “Three Big Ideas” (592 KB PDF) as presented by the Superintendent’s team. This minority report is also available for download (124 KB PDF) –Ed.

Introduction

The Superintendent’s Advisory Committee on Enrollment and Transfer (SACET) was asked to study and report on the “Three Big Ideas” for high school redesign. The three models were presented in broad strokes, with no analysis to support how the models would lower dropout rates, increase graduation or narrow the achievement gap.

The SACET report took note of these shortcomings, but failed to substantially analyze specific information that was given. The committee also failed to supplement given information with readily available data.

Specifically, SACET did not examine the three proposed high school models in light of:

- the clearly stated enrollment and transfer implications of the models,

- the number of campuses that would likely remain open with each model, and

- comparisons to existing high school models in the district and their successes and failures.

The committee also questioned the urgency of the process, which would seem to indicate a failure to appreciate how grossly inequitable our current system is. We don’t, in fact, currently have a “system” of high schools.

This lack of a central system (along with other factors, such as the school funding formula and allowance of neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers), has led to the statistical exclusion of poor and minority students from comprehensive secondary education in Portland Public Schools.

Therefore, it is of tantamount importance that we immediately begin implementing a system that eliminates race, income and home address as predictors of the kind of education a student receives in high school.

For the first time since massive revenue cuts in the 1990s began forcing decentralization of our school system, we are envisioning a single, district-wide model for all of our high schools. That is a remarkable and welcome step toward equity of educational opportunity in Portland Public Schools.

The focus of this minority report is on the three factors listed above: enrollment and transfer, number of campuses remaining, and comparisons to existing high schools.

Analysis of the Models

Special Focus Campuses

Large campuses (1,400-1,600 students) divided into 9th and 10th grade academies and special-focus academies for 11th and 12th grades. Students in 11th and 12th grades must choose a focus option.

Enrollment and transfer implications This model would more or less keep the existing transfer and enrollment model, and depend on an “if we build it, they will come” model to draw and retain enrollment in currently under-enrolled parts of the district by focusing new construction in these areas (per Sarah Singer).

School closure implications This model would support 6-7 high school campuses, leading to the closure of 3-4.

Comparison to existing schoolsThis model would draw on the “small schools” models that have been tried with varying degrees of success at Marshall and Roosevelt, and which have been rejected by the communities at Jefferson and Madison. It would also use the 9th and 10th grade academy model that has been successful at Cleveland.

Neighborhood High Schools and Flagship Magnets

Moderately-sized (1,100 students) comprehensive high schools in every neighborhood, with district-wide magnet options as alternatives to attending the assigned neighborhood school.

Enrollment and transfer implications This model would eliminate neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers, as well as the problems that go with them: self-segregation; unbalanced patterns of enrollment, funding and course offerings; and increased vehicle miles. School choice would be preserved in the form of magnet programs.

School closure implications As presented, this model would support 10 high school campuses, requiring none to be closed.

Comparison to existing schools This model most closely resembles the comprehensive high schools that are the most successful and are in the highest demand currently in Portland Public Schools.

Regional Flex

The closest thing to a “blow up the system” model. The district would be divided into an unspecified number of regions. Each region would have a similar network of large and small schools, with students filling out their schedules among the schools in their region.

Enrollment and transfer implications Transfer between regions would be eliminated, allowing sufficient enrollment to pay for balanced academic offerings.

School closure implications Most high school campuses as we know them would be closed or converted, in favor of a distributed campus model.

Comparison to existing schools This model would draw on both small schools and comprehensive schools currently existing in our district, but as a whole would be more similar to a community college model than any existing high school model in our district.

Recommendation

It is understood that these models represent extremes, and that the ultimate recommendation by the superintendent will likely contain elements of each.

That said, the Neighborhood High Schools model is the closest thing to a truly workable model. If used as the basis of the ultimate recommendation, that recommendation will stand the highest political likelihood of winning a critical mass of community support.

Specifically, the neighborhood model:

- is responsive to high demand for strong neighborhood schools;

- supports a broad-based, liberal arts education for all students, but does not preclude students from specializing;

- balances enrollment district-wide, providing equity of opportunity in a budget-neutral way;

- preserves school choice, but not in a way that harms neighborhood schools;

- reduces ethnic and socio-economic segregation by reducing self-segregation;

- takes a proven, popular model (comprehensive high schools) and replicates it district-wide, rather than destroying that model in favor of an experimental model (small schools) that has seen limited success in Portland (and significant failures);

- preserves the largest number of high school campuses;

- involves the smallest amount of change from the current system, causing minimal disruption in schools that are currently in high demand;

- is amenable to any kind of teaching and learning, including the 9th and 10th grade academies and small learning communities; and

- preserves room to grow as enrollment grows.

This system is very similar to the K-12 system in Beaverton, which has a very strong system of choice without neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers.

The transfer and enrollment aspect of this model is its most compelling feature.

We have learned definitively that when we allow the level of choice we currently have, patterns of self-segregation and “skimming” emerge. These effects are aggravated by the school funding formula and a decentralized system. Gross inequities in curriculum have become entrenched in our schools, predictable by race, income, and address. These factors have also led to a gross distortion in the geographic distribution of our educational investment.

Clearly, in the tension between neighborhood schools and choice, neighborhood schools have been on the losing end. A high school model that includes neighborhood-based enrollment, while preserving a robust system of magnet options, is a step toward rectifying this imbalance.

We’ve also learned (through transfer requests) that our comprehensive high schools are the most popular schools in the district.

As we have experimented over the years with non-comprehensive models for some of our high schools, the remaining comprehensive schools have been both academically successful and overwhelmingly popular. The small schools model, while it has much to recommend, has been implemented in a way that constrains students in narrow academic disciplines, flying in the face of the notion of a broad-based liberal arts education.

There is certainly nothing wrong with small learning communities, but a system that requires students to choose (and stick with) a specialty in 9th or 11th grade is unnecessarily constraining.

A comprehensive high school can contain any number of smaller communities, including 9th and 10th grade academies. Older students may be assigned to communities based on academic specialty, but that shouldn’t preclude them from taking classes outside of that specialty.

The Neighborhood High Schools model clearly does not do everything – our district will remain segregated by class and race. But it would move in the right direction by eliminating self-segregation and beginning to fully fund comprehensive secondary education in poor and minority neighborhoods.

The enrollment and transfer policy could be further tweaked to help reduce racial and socio-economic isolation, as well as to alleviate community concerns that the reduced transfers will lead to poor and minority students being “trapped” in sub-par schools.

To this end, neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers could be allowed, so long as they do not worsen socio-economic isolation. In other words, a student who qualifies for free or reduced lunch could be allowed to transfer to a non-Title I school, and a student who doesn’t qualify for free or reduced lunch could be able to transfer to a Title I school. This is a form of voluntary desegregation that is allowable under recent Supreme Court rulings, since it is not based on race.

Conclusion

All of these models show creative thinking, and, most importantly, a strategic vision to offer all students the same kinds of opportunities, regardless of their address, class, or race. The importance of this factor cannot be overstated.

While none of the models specifically addresses the teaching and learning or community-based supports that are necessary to close the achievement gap and increase graduation rates, they all are designed to close the opportunity gap.

But only the neighborhood model hits the right notes to make it politically feasible and educationally successful: strong, equitable, balanced, neighborhood-based, comprehensive schools, preserving and replicating our most popular, most successful existing high school model, and keeping the largest number of campuses open. The choice is clear.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

18 Comments

May 29, 2009

by Nicole Leggett

Dear Super Team,

I honestly feel that you missed some very clear issues that were expressed at the May 16th meeting.

You can not complete a diverse high school system redesign with out first addressing why it isn’t fair to begin with. The lines that are drawn for our schools need to cross the River. The wealth that lives in two schools should be spread around. Not only so more school have access to more involved parents, but so the students on the West side have access to a diverse community to learn in. Being able to relate to people of differing cultures is best taught young. That is a privilege that is being denied to those children now. In a 21st Century world we all need access to each other to grow to support our city, state, country, world.

Along these lines, it is past time to give neighborhood schools their neighboring enrollment back. It’s time to picture the school down the street as equivalent to the one across town. All it needs is you to make it your neighborhood school. What makes schools better is putting your children and your energy into it. It was clear around the room that neighborhood-to-neighborhood elementary transfers must end. But if honest concerns over quality of education aren’t addressed at the district level this can’t work. We thought that was the job of the K-8 reconfiguration to resolve. Where are the latest audit of K-8 course offerings for this year and next years planning?

As you have said, quality of high school course offerings has to be universal. But as the students explained, the specific educational offerings must to vary to offer specialized learning to motivated youth. So perhaps the idea is to have elementary education equalized and neighborhood focused. But to compliment this idea have an open specialty transfer process at the high school level. Where your neighborhood high school offerings are the same and if you aren’t interested in a magnet program you attend your neighborhood high school. But with the aid of publicly provided transportation, students would be free and able to choose a specialized course offering housed in another school. This would end the Kindergarten scuffle of worried parents that don’t feel comfortable with the feeder pastern of their neighborhood school.

More than anything it was expressed that the highest level of quality education should be offered to all children in all zip codes. Thank you for all of your efforts. Please continue to involve and inform the community at large as we proceed together towards a better tomorrow.

Nicole Leggett is a Peninsula K-8 Parent.

6 Comments

April 14, 2009

by Peter Campbell

In the models for high schools, I see two things that are not being addressed: (1) race/class differences that drive people apart and send some families fleeing from their neighborhood schools, and (2) the reasons why kids drop out of high school. If the design does not address one of the major reasons why families flee, and if it does not address why kids drop out, then the unintended consequences of the current enrollment and transfer policy will be worsened, not improved.

Let me start with race/class differences.

Today, kids in Jefferson are disproportionately low-income and black, whereas in Roosevelt they are disproportionately low-income black and Hispanic. Kids in Lincoln are disproportionately affluent and white. So if we support Model A or B, won’t Lincoln continue to be an affluent white school, Jefferson a low-income black school, and Roosevelt a low-income black and Hispanic school? Since the demographics of the schools are largely reflective of the neighborhoods, then you are likely going to promote racially and economically segregated schools. Is this OK as long as all the schools are high quality?

But given the challenges that schools face that have high concentrations of poverty, can they really be equal in terms of teaching and learning outcomes and produce environments that promote educational excellence? Schools with high concentrations of poverty will need more assistance (e.g., more funding to create smaller class sizes and more guidance counselors), and they may face more challenges. If the additional assistance is not provided and the challenges not met, my concern is that students will want to flee these schools, no matter what their offerings are.

As you recall, not so long ago there were comprehensive high schools and middle schools in low-income areas in PPS. What happened to them?

Students fleeing their low-income neighborhood schools: we all know this has been the unintended consequence of the enrollment and transfer policy. So what are the new models going to do to prevent this from happening?

I would recommend that a program at all of the schools be established that deals explicitly with the issues of racism, poverty, and multiculturalism. If we take the idea of student academies included in the Model A design, these groups of students could be racially and economically diverse. Part of their work together would involve periodic guided conversations with a teacher/facilitator in which the students would discuss racism and poverty and inter-cultural communication. An example of this sort of program is Anytown, sponsored by the National Conference for Community and Justice.

The design would acknowledge the challenge of nurturing and sustaining a diverse learning community and would take the challenge head on. The design would also acknowledge that “white flight” has happened before and can just as easily happen again. So it must take this phenomenon into consideration and deal with it explicitly.

In this way, the high schools will lead the way in promoting larger conversations about how we can nurture and sustain diversity in the larger Portland community. In the end, our high school students would become community role models.

Finally, let me turn to why kids drop out of school.

According to a 2006 Gates Foundation study (1.1 MB PDF) on why kids drop out, nearly half of the kids surveyed said a major reason for dropping out was that classes were not interesting. These young people reported being bored and disengaged from high school. So do the designs increase or decrease interest and engagement? Part of the challenge here is that state law requires that core requirements be met in 9th and 10th grade, with very little room for students to choose classes of interest. Even if the new designs offer everything from anthropology to zoology, the students will not benefit from these diverse offerings until later. So can they wait that long to learn about what interests them? I would recommend an examination of the state law and push for fewer core requirements in 9th and 10th grade.

Another one of the other major reasons cited for why kids drop out is the feeling that no one cared about them. So how do these models promote caring? How do these models allow for teachers to get to know kids and to care for them and care about them? High school teachers currently have 130 to 150 students each. How much can be expected of them in this model? We know that a great teacher is often the critical difference for why kids succeed. So how do these models promote great teachers and great teaching?

If you went with Model A or B, you’d have to hire a lot more teachers to reduce class size and you’d have to budget and schedule for team-based professional development. These are the sorts of critical success factors that a teacher colleague of mine mentioned. As he said, this is not just about “effective structures,” the focus the district has chosen to take. You really do have to consider “Effective People” and “Effective Teaching and Supports” at the same time, the two other areas the district mentioned but has not focused on. Understood that you start with one, but once an “Effective Structure” has been chosen, then these other factors need equal if not more time and consideration.

So I’d like to to slow down the process and take the time to get this done right. We’ve already been through one very hurried, very unplanned redesign process with the K-8 reconfiguration. Let’s not have another. If we don’t redesign our high schools to solve the problems that are inherent in them, then what’s the point?

Peter Campbell is a parent, educator, and activist, who served in a volunteer role for four years as the Missouri State Coordinator for FairTest before moving to Portland. He has taught multiple subjects and grade levels for over 20 years. He blogs at Transform Education.

42 Comments

April 8, 2009

by Steve Rawley

I publish this Web site to advocate for the greater common good. I even came up with a mission statement some time back to capture this notion more specifically:

The mission of PPS Equity is to inform, advocate and organize, with a goal of equal educational opportunity for all students in Portland Public Schools, regardless of their address, their parent’s wealth, or their race.

I’ve been troubled by the direction some recent discussions here have taken, as have some readers who have contacted me privately.

Discussions about poverty and race have pushed some into extreme frustration. One reader sent me this link as an illustration of the attitudes she has encountered on this site.

Another reader chafes at what she perceives as an anti-test bias on this site. She cites data showing “65% of PPS 10th grade black students getting a C or better in math but ODE assessments show[ing] only 21% of that population at benchmark.” There’s huge distrust of the district within minority communities, and this kind of data shows why.

Yes, we’ve seen district policy ostensibly aimed at narrowing the “achievement gap” contribute to a two-tiered school system. But that doesn’t mean the achievement gap isn’t real, that the district can’t take real strides in addressing it, or that we shouldn’t have some objective standards by which to measure the district’s progress in doing so.

This is just one example of where teacher-reformers clash — perhaps unwittingly — with civil rights activists, a fight I don’t want to get in the middle of.

The charter school discussion is another fight I’m weary of. It has veered repeatedly into personal territory, with charter parents getting passionately defensive about their personal choices, and charter opponents criticizing those choices with equal passion. From within that melee, I asked a simple question: How can charters contribute to the greater common good?

Besides modeling pedagogy that we already know works, nobody seems to have an answer to that succinct question (though some have pointed out how charters work against the common good).

At the end of the day, I’m not interested in hosting a pissing match about personal choices. I also don’t want to get too deeply into education reform issues, which increasingly seem to pit progressive-minded teachers against civil rights groups (not to mention their strange bedfellows in the market-oriented, anti-union, foundation- and corporate-funded “reform” movement).

I don’t doubt that education reformers want to help all students, and that charter parents would love a system where everybody wanted and got what they’re getting. But these discussions don’t seem to lead to much unity of vision or purpose.

One thing I know for sure: the enrollment and funding policies of Portland Public Schools have resulted in a pattern of public investment and placement of comprehensive schools that demonstrably favors white, middle class neighborhoods and students, to the detriment of the other half of the city. I’m not naive enough to think righting that wrong would be enough for our poor and minority students; I think the district should learn to walk and chew gum at the same time — i.e. address inputs and outcomes simultaneously.

But this is the focus I want to get back to here: what can we do to make our public school system fair, just and equitable for the greater common good? If we’re not working toward answering that question, I fear we’re getting sidetracked… just as we finally see signs of movement in that direction at the district level.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

58 Comments

March 16, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Portland Public Schools staff will present the five proposed high school system designs to the Superintendent’s Advisory Committee on Enrollment and Transfer (SACET) Tuesday. This will be the first detailed public look at the various models (PDF) being considered for our high school system.

The meeting is 5:30-8:30 pm, Tuesday, March 17 at BESC, 501 N. Dixon, in the conference room L1 on the lower level. Though public is invited to attend, there will not be formal opportunity to participate in the discussion at this time (later public forums have been promised).

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

12 Comments

February 13, 2009

by Steve Rawley

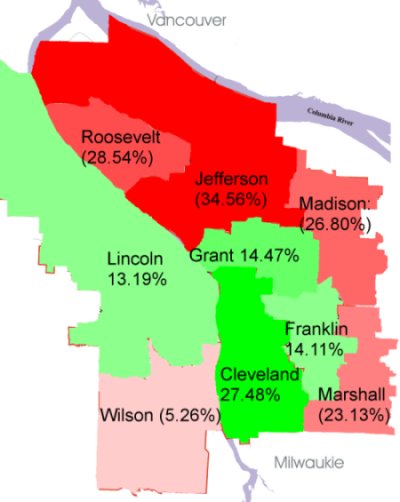

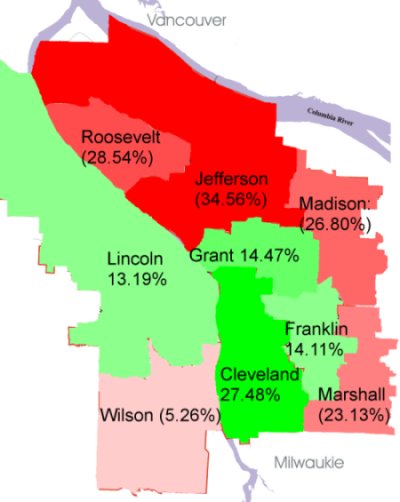

2008-2009 PPS student migration

Percentage of enrollment gained (or lost) due to student migration (compared to cluster population)

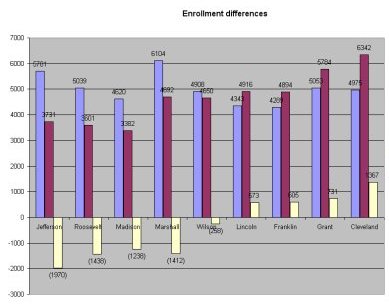

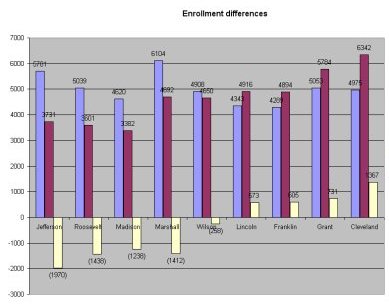

Student population vs. enrollment

Availability of comprehensive secondary schools correlated with race and poverty

| cluster |

# comp. high schools |

# comp. middle schools |

% non-white by residences |

% free/reduced meals by residence |

| Jefferson |

0 |

0 |

67.48% |

61.39% |

| Roosevelt |

0 |

1 |

67.6% |

72.30% |

| Madison |

0 |

0 |

61.95% |

61.77% |

| Marshall |

0 |

1 |

57.96% |

72.79% |

| Wilson |

1 |

2 |

24.57% |

20.80% |

| Lincoln |

1 |

1 |

21.60% |

9.30% |

| Franklin |

1 |

1 |

35.05% |

38.52% |

| Grant |

1 |

2 |

32.85% |

23.17% |

| Cleveland |

2 |

2 |

27.16% |

30.15% |

Note: teacher experience and student discipline rates also correlate highly to race and poverty; that is, average teacher experience is lower and discipline referral rates higher in schools serving high poverty, high minority populations. Data for the current school year are not yet available for these factors.

Data source: Portland Public Schools.

This report is available in PDF format (240KB).

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

15 Comments

« Previous Entries Next Entries »