Category: Features

March 28, 2010

by Steve Rawley

It is with both sadness and a sense of great relief that I tell you this will be the final post on PPS Equity. [Here’s Nancy’s farewell.]For two years we have documented inequities in Portland’s largest school district and advocated for positive change. Along the way, we’ve explored how to use new media tools to influence public policy and foster a more inclusive form of democracy.

The reason for this shutdown is simple: we are moving our family out of the district, and will no longer be stakeholders. A very large part of our decision to leave is the seeming inability of Portland Public Schools to provide access to comprehensive secondary education to all students in all parts of the city. We happen to live in a part of town — the Jefferson cluster — which is chronically under-enrolled, underfunded and besieged by administrative incompetence and neglect. We have no interest in playing a lottery with our children’s future, and no interest in sending our children out of their neighborhood for a basic secondary education. These are the options for roughly half of the families in the district if they want comprehensive 6-12 education for their children.

While there are some signs that the district may want to provide comprehensive high schools for all, there is little or no acknowledgment of the ongoing middle grade crisis. If the district ever gets around to this, it will be too late for my children, and thousands of others who do not live in Portland’s elite neighborhoods on the west side of the river or in parts of the Grant and Cleveland clusters.

It cannot be understated that the failure of PPS to provide equally for all students in all parts of the district is rooted in Oregon’s horribly broken school funding system, which entered crisis mode with 1990’s Measure 5. A segregated city, declining enrollment and a lack of stable leadership and vision made things especially bad in Portland.

But Portland’s elites soon figured out how to keep things decent in their neighborhoods. The Portland Schools Foundation was founded to allow wealthy families to directly fund their neighborhood schools. Student transfers were institutionalized, allowing students and funding to flow out of Portland’s poorest neighborhoods and shore up enrollment and funding in the wealthiest neighborhoods. Modest gains for Portland’s black community realized in the 1980s were reversed as middle schools were closed and enrollment dwindled. A two-tiered system, separate and radically unequal, persists 20 years after Measure 5 and nearly 30 years after the Black United Front’s push for justice in the delivery of public education.

PPS seems to be at least acknowledging this injustice. Deputy Superintendent Charles Hopson laid it out to the City Club of Portland last October: “It is a civil rights violation of the worst kind… when based on race and zip code roughly 85% of white students have access to opportunity in rigorous college prep programs, curriculum and resources compared to 27% of black students.”

Despite this acknowledgment, the district is only addressing this inequity in the final four years of a K-12 system. We don’t, in fact, have a system, but a collection of schools that vary significantly in terms of size, course offerings, and teacher experience, often correlating directly to the wealth of the neighborhoods in which they sit.

As the district embarks on their high school redesign plan, which is largely in line with my recommendations, predictable opposition has arisen.

Some prominent Grant families rose up, first in opposition to boundary changes that might affect their property values, then to closing Grant, then to closing any schools. (They seem to have gone mostly quiet after receiving assurances from school board members that their school was safe from closure. Perhaps they also realized that they have more to fear if no schools are closed, since it would mean the loss of close to 600 students at Grant if students and funding were spread evenly among ten schools. In that scenario, the rich educational stew currently enjoyed at Cleveland, Grant, Lincoln and Wilson will be a thinned out to a thin gruel. It would be an improvement for the parts of town that long ago lost their comprehensive high schools, but a far cry from what our surrounding suburban districts offer with the exact same per-student state funding.)

There is also opposition from folks who reflexively oppose school closures, many of them rightly suspicious of the district’s motivations with regards to real estate dealings and their propensity to target poor neighborhoods for closures.

Finally, there is opposition on the school board from the two non-white members, Martín González and Dilafruz Williams.

González’s opposition appears to stem from the valid concern that the district doesn’t have a clue how to address the achievement gap — the district can’t even manage to spend all of its Title I money, having carried over almost $3 million from last year — and that there is little in the high school plan that addresses this. (It’s unclear how he feels about the clear civil rights violation of unequal access this plan seeks to address. It seems to me we should be able to address both ends of the problem — inputs and outcomes — at the same time . The failure to address the achievement gap should not preclude providing equal opportunity. It’s the least we can do.)

Williams noted that she doesn’t trust district administrators to carry out such large scale redesign, especially in light of the bungled K-8 transition which she also opposed. It’s hard to argue with that position; the administration has done little to address the distrust in the community stemming from many years of turbulent and destructive changes focused mainly in low-income neighborhoods.

But more significantly, Williams has long opposed changing the student transfer system on the grounds that it would constitute “massive social engineering” to return to a neighborhood-based enrollment policy. Ironically, nobody on the school board has articulated the shameful nature of our two-tiered system more clearly and forcefully as Williams. But as one of only two non-whites on the board, Williams also speaks as one of the most outwardly class-conscious school board members. In years past, she has said that many middle class families tell her they would leave the district if the transfer policy were changed.

(Note to director Williams: Here’s one middle class family that’s leaving because of the damage the transfer policy has done to our neighborhood schools. And it’s too bad the district can’t have a little more concern for working class families. I know quite a few parents of black and brown children who have pulled their kids from the district due to its persistent institutional classism and racism.)

Williams (along with many of her board colleagues) has also long blamed the federal No Child Left Behind Act for the massive student outflows from our poorest schools, but this is a smokescreen. Take Jefferson High for example, which was redesigned in part to reset the clock on NCLB sanctions. Yet despite this, the district has continued to allow priority transfers out. Jefferson has lost vastly more funding to out-transfers than the modest amount of Title I money it currently receives. If we don’t take Title I money, we don’t have to play by NCLB rules. (This is not a radical concept; the district has chosen this course at Madison High.)

It is hard to have a great deal of hope for Portland Public Schools, despite some positive signals from superintendent Carole Smith. We continue to lack a comprehensive vision for a K-12 system. English language learners languish in a system that is chronically out of compliance with federal civil rights law. The type of education a student receives continues to be predictable by race, class and ZIP code. Special education students are warehoused in a gulag of out-of-sight contained classrooms and facilities, and their parents must take extreme measures to assure even their most basic rights. Central administration, by many accounts, is plagued by a dysfunctional culture that actively protects fiefdoms and obstructs positive change. Many highly influential positions are now held by non-educators, and there is more staff in the PR department than in the curriculum department. Recent teacher contract negotiations showed a pernicious anti-labor bias and an apparent disconnect between Carole Smith and her staff. Principals are not accountable to staff, parents or the community, and are rarely fired. Positions are created for unpopular principals at the central office, and retired administrators responsible for past policy failures are brought back on contract to consult on new projects.

If there is a hope for the district, it lies in community action of the kind taken by the Black United Front in 1980. The time for chronicling the failures of the district is over.

In his 1963 Letter from Birmingham Jail Martin Luther King Jr. wrote: “In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action.”

I think this Web site has served to establish injustice. Many of us have tried to work with the district, serving on committees, testifying at board meetings, and attending community meetings. My family has brought tens of thousands of dollars in grant money and donations to the district, dedicated countless volunteer hours, and spent many evenings and weekends gathering and analyzing data.

There is no doubt that injustices exist, and there is no doubt that we have tried to negotiate. It’s time for self-purification — the purging of angry and violent thoughts — and direct action. It’s time to get off the blogs and take to the streets.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

Comments Off on The end of the line

November 30, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Sheila Wilcox had a problem. She was teaching eighth grade at a newly expanded elementary school, its first year with eighth grade. The building did not have adequate physical space for the middle grades, and the staff had almost no training or advice on teaching a self-contained middle grade class within an elementary school.

This was in 2008-09 school year, a year after Carole Smith, the newly hired superintendent, had formed a “K-8 Action Team,” and several months after that team had held a public meeting. Wilcox went to the team’s Web page and found somebody at the district office to e-mail.

Wilcox said she wrote to Sara Allan, listed as the project manager for the K-8 team, and told her: “I’m stuck out in a portable, I have no computers, I have no books, I’m teaching eighth grade.”

It took a week to get a response, said Wilcox, and she got no answers to her specific questions. She was told the district was trying to work with the K-8 schools to get the best programs in place. But there was nobody from the district working with teachers at her school, and she didn’t know who else to call.

Wilcox had also noticed that the K-8 team’s Web site listed courses her school had never offered and had no plans to offer. When she notified the district, they said it was data from the previous year, and it would be updated. It never was.

Sara Allan led the K-8 action team, along with two senior administrators: Joan Miller, a part-time retired administrator; and Harriet Adair, a full-time area director, supervising principals at several schools. The team held a series of community meetings in the 2007-2008 school year, and claimed to address some serious issues like libraries, algebra and science labs. The team showed competence in things like middle grade scheduling, but never fully accounted for the actual deficiencies of existing K-8 schools, or presented any real analysis of the scope and depth of the K-8 problem.

After a May 2008 community meeting, the K-8 Action Team went quiet. No more meetings were held, and no announcements made.

K-8s hadn’t stopped being a crisis in the community, but they seemed to have dropped off the district’s radar.

How did we get here?

The root of this problem was the rushed addition of middle grades to most elementary schools in the district, a process phased in over the previous three school years with virtually no planning or sense of a unified model. Principals were going it alone with no district support. Some middle schools were also converted, with the addition of primary grades. These schools managed the change relatively well, at least for middle grade students, since there were, in many cases, enough students to continue funding a comprehensive middle school program.

But most of the elementary schools that converted to K-8s have continued to fare poorly, many with largely self-contained classrooms and few, if any, electives. And as it happened, these “ele-middles” (as coined by parent Lakeitha Elliot) are concentrated in poor and minority neighborhoods.

Middle schools were preserved in some parts of Portland. Eight of the district’s 10 remaining middle schools — Beaumont, da Vinci, Hosford, Jackson, Mt. Tabor, Robert Gray, Sellwood and West Sylvan — are located in majority white high school clusters (Cleveland, Franklin, Grant, Lincoln and Wilson). A total of two, George and Lane, remain in the district’s four majority non-white attendance clusters (Jefferson, Madison, Marshall and Roosevelt).

PPS claims they have not tracked the demographics of middle grade students assigned to and attending K-8 schools, compared to middle schools. (I requested this demographic information from Public Information Officer Matt Shelby, and Sarah Carlin Ames, Director of Government Affairs. Shelby wrote in e-mail that the district is unable to fulfill my request.)

But it is clear, extrapolating from available data showing middle schools to be disproportionately white and non-poor when compared to the general PPS student population, that middle grade students at K-8 schools are conversely poor and non-white.

Deputy Superintendent Charles Hopson recently told the City Club of Portland that “based on race and zip code roughly 85% of white students have access to opportunity in rigorous college prep programs, curriculum and resources compared to 27% of black students.” Even without the direct, hard data from the district, we can see the same is true about access to comprehensive middle school programs.

The largest stretch between middle schools in Portland is the eight and a half miles between George middle school in North Portland and Beaumont in Northeast. This stretch spans historically poor and working class neighborhoods, and includes all of historically black Portland.

Org chart changes

With the new school year in 2009, the district announced major org chart changes, including a promotion for Sara Allan, to “Senior Director of Planning and Performance Management,” reporting directly to Carole Smith and supervising a senior management team (three with the title of Director, plus two “Advisor[s] to the Superintendent” and three “Senior Managers”) in charge of everything from high school redesign to data and policy analysis. Harriet Adair, once an assistant superintendent, is now listed as an “Advisor to the Superintendent” on K-8 redesign, reporting to Allan.

Other than Adair, who also advises the superintendent on early childhood issues, it appears the K-8 Action Team no longer exists in any significant, working form.

Its Web page is no longer prominently linked on the district Web site, which has since undergone a redesign. But the page still existed as of publication of this article, listing these objectives to be completed by August 2008:

- Work to identify critical operational supports for PK-8 schools in the 2008-09 year and develop strategies to fill gaps in the following areas.

- Staffing

- Enhancements to facilities

- Professional development for teachers

- Student support

- Design a common districtwide PK-8 model and set of guidelines for grades 6-8 education and define a plan to build the required elements over the next three years.

- Create a process to engage schools and the community in the vision and the plan.

It’s unclear if any of this work has been completed more than a year after its targeted completion. Allan said the team continues to exist, albeit without any dedicated, full-time staff.

“There’s lots of ongoing planning around how do we continue to make sure that all of our 6-8 programs are very comparable in terms of what opportunities students have,” said Allan. “They’re constrained by the resources that we have available, but there’s definitely ongoing work around insuring that we have consistent programs in all places so that kids are equally prepared for high school.”

Allan also said there is “a lot of work going on analyzing how we do staffing allocations.” Despite this work, K-8s continue to operate on the same staffing allocation as middle schools, which, with their much larger student cohorts, are able to offer dramatically more curriculum for the same money per student.

Just under half of the district’s middle grade students currently have access to a traditional middle school in their neighborhood. Would it make sense to go back to a middle school model for the entire district, or at least make sure that all students have access to a nearby middle school?

“I think the question is, is the structure of the middle school the answer, or is it what’s happening in the classrooms?” said Allan.

She said that by bringing middle grade student populations up to a minimum of 150 students, and with adjustments to the staffing formula, all middle grade students can have access to the same kind of education, regardless of the configuration of their school. That means the district will have to shift funding from middle schools, or “equalize down”, in order to provide even a basic middle grade experience in the K-8 schools.

Under the current funding formula, 150 students provide enough budget for about six teachers for the middle grades, enough to basically do self-contained classrooms. Astor, where Wilcox teaches, has around that number of students.

With an adjusted staffing formula, would there be any way to pay for electives like instrumental music and world languages for every K-8 school?

“That is the stuff we’re looking at specifically,” said Allan.

Rebecca Levison doesn’t buy it. She’s a teacher with experience in a self-contained middle grade classroom, and the current president of the Portland Association of Teachers, the union representing the district’s teachers.

There is no way, Levison contends, that the district’s K-8 schools will offer anything close to what is currently offered in middle schools.

The district’s K-8 strategy centers on retaining and building middle grade enrollment up to 150 students. That, combined with an adjusted staffing formula, appears to be the extent of planning to deal with a problem that is well into its fourth year.

It’s not clear if there is any plan to have an adjusted staffing formula in place, or to increase enrollment for the 2010-11 school year, the fifth year of K-8 implementation.

Choice and equity

Over the years, as the district has experimented with a market-oriented, competition-based student enrollment system, schools in poor and minority neighborhoods lost significant enrollment, funding, and curriculum. Jefferson High School, Oregon’s only majority black high school, had an attendance area population of just over 1,500 in fall of 2008. Approximately 500 high school students enrolled that year, with nearly 1,000 transferring out under the district’s liberal school choice policies.

Then, as now, Jefferson’s course catalog reflected this loss of enrollment and funding. At the former arts magnet school, there were no music classes offered, no advanced placement classes, no chemistry, physics, or calculus, and no world languages other than Spanish.

The district has had no real strategy for dealing with this self-reinforcing spiral of declining enrollment and opportunity brought on by allowing students to freely transfer from one neighborhood school to another. Disproportionately non-white and poor schools like Jefferson were told they had to increase enrollment in order to replace lost courses. But without a reasonable course catalog, these schools didn’t have much in the way of recruitment tools.

Vicki Phillips, who preceded Carole Smith as superintendent, promoted school choice as a tool for equity in spite of overwhelming evidence of the damage it did to schools in poor and minority neighborhoods. Smith’s plan for high schools tacitly acknowledges the failure of this policy.

Under Smith, the district has announced a high school plan that would bring comprehensive schools to all, and significantly do away with the market-based strategy of choice and competition for enrollment pushed under Phillips, at least for high schools.

The plan would implement a high school system based on neighborhood enrollment, with student transfers restricted to guarantee similar school sizes and funding. This would also ameliorate the significant self-segregation that has resulted in schools more segregated today than thirty years ago.

Every student, or so the plan says, will have access to comprehensive neighborhood high schools of about the same size and with the same range of programming, including courses for college credit, instrumental music, choral music or dance, and a choice of world languages. This would be a major upgrade for schools in our poorest neighborhoods, and represents an important acknowledgment of a basic economic reality.

The free market approach to enrollment and funding is a demonstrable failure in Portland, when measured by access to educational opportunity. Unless the district is willing to significantly reduce opportunity for the white middle class, there’s no way they can pay for equity of opportunity without balancing enrollment, that is, by curtailing school choice. This is a significant element of the high school plan. With it, the district appears to be forging a path independent of current trends pushed by Gates, at least for high schools.

But the district appears unwilling to apply the same lesson to middle grades.

Sara Allan’s contention that it’s not the structure of the school that matters, but what goes on in the classroom, also closely parrots the current line being sold by Phillips, now head of education for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Phillips was the keynote speaker at the Council of The Great City Schools conference held in Portland last month, attended by Allan and quite a few of her administrative colleagues. In her speech, Phillips promoted merit pay for teachers, the latest policy thrust of Gates.

While superintendent in Portland, Philips was responsible for both the transition to K-8 schools and the “small schools” initiative, funded largely by the Gates foundation, which dismantled every comprehensive high school in Portland serving majority non-white students, and split them into rigid “academies.” These academies forced students to choose a narrow field of study as freshmen, and didn’t allow students to take electives offered in other academies in the same building.

When combined with Phillips’ dogmatic fealty to school choice, comprehensive secondary education was thus eliminated for the majority of poor and minority students in Portland. Students who are white and wealthier are statistically more likely to take advantage of student transfers, so schools re-segregated even as attendance areas reintegrated and gentrified. With funding following students, and with rules in place to allow wealthy families to directly fund public schools in their neighborhoods, access to comprehensive secondary education was preserved for the majority of white students in Portland, even while it was eliminated for everybody else.

To date, we seem stuck with this legacy of Vicki Phillips, despite some positive talk about equity of opportunity: We continue to have a clearly defined two-tiered education system, particularly in the secondary grades, with ZIP code, race and class primary determinants of access to a broad-based secondary education.

Gates’ quiet partner

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has grown to be the dominant voice in the national education dialogue, heavily influencing the federal education policy of both George W. Bush and Barack Obama. But even as PPS appears to be taking a non-Gates path on high schools, the district continues to be enamored with Gates’ biggest private-sector education policy ally: Eli Broad’s education foundation.

In 2003, the Broad Foundation started a residency program to lure management professionals into the field of public education. Founded by real estate magnate Eli Broad in the 1960’s, the foundation’s mission is “to advance entrepreneurship for the public good in education, science and the arts.”

The Broad Residency in Urban Education promises young MBAs with as little as four years’ work experience a package that might otherwise take a career to attain: a full-time, senior-level management position in a large urban school district (or charter management organization), reporting to the superintendent or top executive, and a salary of $85,000 – $95,000.

For two years, Broad pays half the residents’ salaries. The school district picks up the other half, plus the cost of benefits. After two years, the district is expected to keep the residents in their jobs, or promote them, picking up the full tab for their salaries.

Over the course of these two years, Broad flies its residents to eight quarterly trainings held at various locations around the country. Residents study topics like “Accountability and empowerment of schools,” “Influence using formal and informal authority” and “Initiating and sustaining large-scale change initiatives.”

The Broad Foundation, whose motto is “Transforming urban K-12 public education through better governance, management, labor relations and competition,” makes no bones about its support of charter schools and its desire to weaken teachers’ unions.

This ideology is couched in rhetoric about “student achievement,” especially among minority students, but Eli Broad himself is clear about his goals. Despite studies showing no improvement for students in charter schools, Broad’s strategy relies strongly on promoting them. Broad spoke at the Michigan Governor’s Education Summit in 2004.

“We believe that healthy competition has raised the quality of higher education in the U.S. and can do the same for our K-12 public school system,” said Broad. “Michigan is to be congratulated for being one of our nation’s leaders in providing parents with competitive education alternatives, through public charter schools.”

Also at the top of Broad’s agenda is eliminating seniority for teachers, and instituting merit pay, or, in today’s parlance “pay for performance.”

“Many labor unions have become obstructionist in holding teachers accountable for student performance,” Broad told his Michigan Audience. “We have to start compensating teachers on a performance basis rather than on seniority. I know that some unions don’t like to hear that, but introducing true accountability is essential to ensuring that student performance improves.”

This amounts to blaming teachers for the overwhelming effects of poverty in the lives of students.

“Student performance,” entirely measured by standardized test scores, correlates highly to poverty. Broad’s scheme would almost certainly assure that teachers in poor and minority communities would make less than their colleagues in wealthier schools, only worsening the achievement gap. This puts the lie to Broad’s (and Gates’) stated mission of closing that gap.

This kind of disconnect between Broad’s stated vision and his policy thrust hasn’t deterred Portland, a strongly blue collar town with high public support for organized labor, from welcoming Broad into its main school district.

Portland Public Schools has hosted four Broad Residents. One left after his residency, one is still in her residency, and two hold key strategic leadership roles overseeing the future of our schools.

Sarah Singer came to PPS five years out of graduate school in 2007, and led the high school system redesign planning over the past year or so (newly-hired Chief Academic Officer Xavier Botana appears to now be taking a more prominent role). Singer has two Masters’ degrees, but no prior professional experience in K-12 education. She makes $90,000 a year. (Top of scale for a teacher, with a PhD and twelve years’ experience, is around $70,000.)

The other is Sara Allan, who came to PPS as a Broad Resident in 2005, and worked at first in human resources and as a project manager. The K-8 Action Team was her first high-profile project. As an executive director she currently works part-time (80 percent) and is paid $90,000 a year. Her base salary of $112,500 is twice what many teachers make with an equivalent level of education. She never worked in a school or school district prior to joining PPS, and has no professional training in K-12 education.

District: No Broad Influence on Policy

Despite the Broad Foundation’s overt ideological thrust, Allan insists that Broad is not trying to push it on PPS.

“It’s really not just ‘bring corporate America to the schools’ at all,” said Allan. “It’s really very much a nuanced thing.”

Second-term school board member David Wynde agrees. He and his school board colleagues attended a Broad-sponsored retreat for in Los Angeles in 2003, in which Eli Broad addressed the attendees.

“There was no advocacy about policy content,” said Wynde. “They weren’t pushing a particular policy agenda. What they were pushing was [school] boards learning how to govern and what it meant to be an effective board, which is a good thing.”

Chief of Staff Zeke Smith acknowledges Broad’s political positions. “It would be silly of me to say that Broad doesn’t have any sort of ideological perspective in what they do,” he said, but he discounts that influence in PPS.

“I think they have an agenda in terms of putting people in a district and wanting to see innovation and change in those districts,” said Smith. “I think that’s why they’re bringing business leaders, but I think that’s also why they’re fairly open about what it is that you get. But I don’t think they’re prescriptive about what that is.”

Smith said the people PPS has hired out of Broad’s program bring “significant experience with project management, and that’s not necessarily a capacity that is well-developed inside of districts. So what we’ve gotten from that is people who understand how you take kind of large complicated issues that need a lot of different stakeholders — internal or external or both — to be involved, and put together a process whereby you can actually get to some real action steps and do it with some level of integrity.”

But can’t people with an education background manage complicated issues?

“Most people who work inside of a school district all the way up to the top have made their way to those positions from an education background,” said Smith, “and people value the idea that, ‘Hey, I was a teacher, then moved up the ranks to assistant principal, and then a principal, and then into administration,’ and there’s a lot of skills that they develop in those places; there’s a lot of skills that they’re exposed to through their classical academic training. Project management isn’t necessarily one of those.”

Smith also said it’s not just the corporate philanthropists pushing charters and merit pay. “We’ve actually got people inside of the White House and inside the administration who are probably going to push us more on those discussions and conversations than Broad has,” he said.

Indeed, the policy positions of Broad and Gates have been broadly adopted by the Obama Administration under Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. The Race To The Top Initiative promises $4.35 billion to states, so long as they are amenable to merit pay and charter school expansion.

Broad’s foundation has maintained close ties to national policy makers of both political parties; its board of directors is a who’s-who of “reformers,” cozy with the current administration and its predecessors, who mainly tout charter schools and merit pay as salves for what they call “the education crisis.” The bipartisan board is chaired by New York City Public Schools Chancellor Joel Klein and includes former Cabinet Secretaries from George W. Bush (Margaret Spellings) and Bill Clinton (Henry Cisneros). Washington D.C. schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee, well-known for her extreme merit pay programs, also serves on the board, as does Richard Barth, President and CEO of the KIPP foundation, a nationwide charter management organization with 82 charter schools, and Wendy Kopp, CEO of Teach for America, an organization that brings non-certified teachers to poor and minority schools.

A major thrust of the Broad Residency is the need for better management in the central office of school districts. Most district offices, it goes without saying, are full of former teachers in administrative roles. Teachers, Broad seems to think, can barely be trusted in the classroom, and they certainly aren’t qualified to be promoted into positions in control of large amounts of money.

Broad’s recruiting material spells it out: “Many school districts are the size of Fortune 500 companies. They need leaders and strong managers who understand the complex operations of a large organization—successful professionals with experience in human resources, operations, finance, strategic planning and other critical business areas.”

In Portland, one teacher, who prefers to remain anonymous, claims she overheard former Broad Resident Sarah Singer joke that being “education free” was a major qualification for leading education system redesign. (Singer denies having said this.)

The Teacher’s Union

Teachers and PAT are currently deadlocked over terms of a new contract to replace the one that expired in 2008. The two-year contract they are currently negotiating will expire in seven months, assuming they reach an agreement by then. A key sticking point is the district asking for more hours and more scheduling flexibility from teachers, while refusing to budge on salary.

“We’ve had a lot of formal conversations,” said Levison, the teachers’ union president, “and there has been absolutely no movement on their side. You can’t ask to increase somebody’s work day while simultaneously cutting their salary.”

Levison was surprised to encounter former Broad Resident Allan at the bargaining table, and questioned her qualifications.

“I don’t think you’re qualified for school administration if you haven’t been in the classroom,” said Levison. “Someone who is working in education needs to have background and experience, otherwise they’re making decisions at the 30,000 foot level.”

Allan acknowledges she is “part of the bargaining team, providing background analysis,” and defends her lack of educaton experience. “The key role my department plays is more about project management, organizing a process rather than trying to know the answer,” she said.

Allan said her role is more one of process rather than policy. “It’s a diverse group of people that are on the bargaining team that all are contributing,” she said, “and so I might be playing a role of packaging and presenting.”

But Levison sees a pattern in the current administration of making decisions that do not take into account the realities faced by teachers, students and families. She cites the scheduling of several school days this year with two-hour late openings, a top-down decision made without input from the district’s scheduling committee, as another example.

“They don’t understand how it impacts teachers’ workloads, how it impacts students, and how it impacts parents,” said Levison.

Teachers are accustomed to tough-on-labor negotiating from the district, but it especially stings coming from a young MBA with no background in the field making a base salary 60 percent higher than the most senior, most qualified teacher in the district.

“There’s a level of anger when teachers are working harder than ever, and they see Broad scholars and senior managers getting raises,” said Levison. “It increases the anger.”

While the superintendent’s office claims the district’s recent central office reorganization cut more than 10 administrative positions worth a million dollars, Levison disputes their figures. She says there is a tendency to create positions for displaced administrators rather than laying them off.

While several “area director” positions were eliminated, none of the administrators were let go or faced pay cuts in their new roles, even with reduced responsibilities. Harriet Adair was an area director last school year, directly supervising principals at several schools. Adair now has no staff directly reporting to her, according to Zeke Smith.

A teacher, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the joke in the schools is that “they put so-and-so in the basement of BESC sorting paper clips.”

When teachers demonstrated en masse at a recent school board meeting, they made an issue of the $15,268 raise administrator Robb Cowie got when he was promoted to Executive Director of Community Involvement and Public Affairs under the reorganization. The presence of highly-paid Broad staff at the bargaining table has further poured salt in the wound.

“I think there’s absolutely more they can cut,” said Levison. “None of these cuts are going to fill the hole, but when a Broad resident is making whatever they make, that’s an art teacher. That’s a music teacher. That’s a special ed teacher. That’s a special ed teacher and a para-educator.”

Levison is particularly irked at the way the district has dropped the ball on K-8 schools. “To ignore this huge disparity in K-8s and move on to high schools is just criminal,” she said.

Accountability: only for teachers?

While corporate philanthropists tout the importance of teacher accountability for student achievement, there doesn’t seem to be much accountability for their own failed reform efforts.

A commonly voiced perception in the community and in schools is that the K-8 model is a failure and that the K-8 Action Team has gone dormant. I asked Allan, now the person in charge of performance management for the district, how she would rate the performance of the K-8 Action Team.

“We’ve done a fairly lousy job,” she said, “in continuing to kind of engage with the community around this so they know what we’re doing, and they’re seeing it. I think we’re not necessarily hearing from them in terms of the same heightened level of concern as the K-8s have kind of matured a little bit, but that certainly doesn’t take the responsibility off us not to be doing a better job at engaging. So I would give us a bad grade on that.”

She claims some success with the K-8 model, and says there is no plan to go back to the middle school model that has been preserved in the wealthiest Portland neighborhoods.

“We don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water,” Allan said.

“We’ve just been doing a big study on how’s student achievement doing at the K-8s versus the old middle schools, and there’s definitely some really good early indicators there in terms of closing the achievement gap,” said Allan. “We’re starting to see that some of our best results are coming out of K-8 schools.”

But this claim of K-8 success seems dubious, with the district unable to account for the demographics of middle grade students attending K-8 schools and with persistent and marked differences in the level of education on offer.

At Astor K-8 school, Wilcox said she and her colleagues had their break room converted to a classroom this year due to lack of space, a violation of their contract. Eighth grade continues to be taught in self-contained classrooms in portables on the playground, and there is still little in the way of central support for teachers.

Meanwhile, district leaders, fresh from Broad, assure teachers everything is under control in K-8 schools and demand more teacher flexibility in contract negotiations.

Pay no attention to the men behind the philanthro-capitalist curtain, their anti-teacher ideology and their solid track record of gutting public education for poor and minority students in Portland. This is education “reform,” and it’s all about closing the achievement gap.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

53 Comments

September 16, 2009

by Bonnie Robb

I am a teacher at Harrison Park Elementary (formally Clark K-8 @ Binnsmead). Our demographics include a wonderfully diverse population with students from over 20 countries. I have seven languages represented in my room alone. We also have 80% of our families receiving free or reduced lunch benefits, which places us in the top 15% highest poverty schools in the district. At least 50% of our parents speak a language other than English. I am beginning my ninth year working with our wonderful families.

We have always had to limit our extra activities, such as field trips, with our students. We received some money ($75-$100) for each class for field trips each year, and our school budget helped cover some overages. Of course, buses are $200 each in addition to admission to events, so we still had to ask parents for contributions for field trips, although no child was denied a field trip due to lack of funds. We usually had to ask for less than five dollars per child, and most could contribute that much. These field trips were memorable, and for some of my first graders, the first time they had crossed a bridge over the Willamette River.

We recently were reminded by the district that we cannot require students to contribute to field trip costs, and we have to make sure the parents know this. Also, our school no longer has a PTA to raise funds for the school. Basically, there is no money for field trips from the school or PTA. Our district has not helped with field trip costs for years.

I have written/applied for many grants to help enrich my classroom, last year supplying the funds for a $900 field trip through a Donors Choose grant. Many of our teachers go the extra mile (and take personal time, thank you) to write/apply for grants so our disadvantaged students can experience a world outside of their neighborhood.

It is a fact that more affluent schools have PTAs and fund raising mechanisms in place to provide money to their teachers for class field trips, visitors and supplies. It is great that the parents at these schools have the money and time to supplement their child’s educational experience. As far as I am aware, our district perceives no problem with this status quo.

However, this district is charged to provide an equal education to all. Our leadership tries to do this with a canned curriculum, but when students who already come to school with a wealth of experience and opportunities continue to receive more of these rich experiences at school (due to luck of birth or the location of their home) the gap of equity widens. Children in poverty enter school at least two years behind in skills and language development. Rich curriculum and real experiences can help with that gap, but when there is no money for extra-curricular activities unless they can be raised by the families they benefit, our poor children stagnate, our rich children grow. Once again, families that can afford more, and already do more, get more for their children in our “free and public” educational system.

Is there a solution to this problem? Perhaps if all students do not have an opportunity for field trips, no students should. If our students cannot raise money for field trips, perhaps none should be able to raise money. Maybe the district could pay one administrator 10k less and pay for one field trip a year for each class in a poverty school. Well, I am sure that will not happen, so I will go ahead and try to write more grants so my students can attempt to have an educational experience equal to their more affluent peers. They deserve nothing less.

Bonnie Robb teaches at Harrison Park Elementary. She is a recent recipient of the Milken Family Foundation National Educator Award.

27 Comments

June 30, 2009

by Sheila Wilcox

Everyone’s a critic, it’s true. It is easy to point fingers, but try to fix something? This takes more effort than most people can muster.

I have been a witness, for the last four years, to Portland Public Schools’ fiasco known as K-8 schools. I have tried to shed light on the problems created by this policy and had hoped to, as they say, be part of the solution, not part of the problem. The district has a history of not accepting blame when it is due, continuing with programs proven not to work, and trying to spin it all in a positive light. As PPS entrenches itself deeper into this hole it has dug itself, I cannot help but throw in my two cents, both as a K-8 teacher in PPS, and as a parent to two children in a K-8 school.

Perhaps the most obvious problem with K-8s is that the facilities housing them are woefully inadequate. My school this year, as of June 12, is losing its staff room to a classroom and the nurse will be in the hall. We were promised a brand new computer lab, but alas will have to settle for a mobile cart of computers to be wheeled from classroom to classroom. There is no science lab, our library is extremely small, and the counselor has to share a room with several other programs. Already, there is a portable on the playground. It is true that some schools have enough space, but many do not.

Indeed, some schools have scaled back their K-8 plans due to space constrictions. However, this policy is not applied consistently. Several times, in other K-8s I have taught, facilities people have gone on walk-throughs to plan for the upcoming years. Never have I seen staff asked for input. Indeed, I have seen several staff members give input, only to have it ignored. This resulted in configurations that then had to be changed once the school year started.

Even if facilities for K-8s were sufficient, the content taught and the approach to this content is not at all up to the standards of most middle schools. Many middle schools in K-8s are taught using a self-contained model. This means that one teacher teaches almost all subject matter. The problem with this is that the higher the grade level, the more complex the subjects become, and most teachers, no matter how gifted they are, cannot adequately teach every subject.

Most middle school teachers teach one or two subjects. They are experts in those subjects. As a parent, I want my children to learn from experts. Additionally, electives are taught, usually, by those same teachers. So, on top of teaching 4-5 academic subjects, middle school teachers in K-8s are required to teach an additional elective. Hence, lots of knitting, badminton, and study halls are offered. No music, no home economics or languages, as these would require actually hiring additional teachers.

Lastly, in addition to lacking satisfactory facilities and academic support, K-8s have no one steering the boat, so to speak. Most administrators are trained in elementary protocols and procedures, not middle school models. I have called several people in the district who were supposed to be “in charge” or helping those in charge, and have gotten nowhere.

The last phone call I made, on June 12, was to a facilities person. She got irritated with me asking “Why do we not have adequate room for our programs?” She then started asking me what my solutions were. I offered two or three, and she said each one had already been considered and thrown out. But it left me wondering. If you really wanted my opinion, as a teacher in a K-8, why didn’t you ask me four years ago?

Sheila Wilcox is a PPS parent and K8 teacher.

52 Comments

June 15, 2009

by Steve Rawley

Note: The Superintendent’s Advisory Committee on Enrollment and Transfer (SACET) was asked to study and report on the high school system redesign. The SACET report (67 KB PDF) was issued in May, with the full support of 12 of 14 members of the committee. One member supported the report with some questions, and one member, your humble editor, could not support the report.

There was no official mechanism within the committee to issue a minority report, so this report is an ad hoc response to the shortcomings of the SACET report. As a member of that committee, I bear a share of responsibility for these shortcomings, so this report is not intended as a personal attack on any of my committee colleagues who spent a great deal of time and energy on a report that reflects much that I agree with. Rather, it seeks to cover areas that SACET did not cover, and amplify their call for “a plan that has neighborhood schools as its foundation.”

This report refers to the “Three Big Ideas” (592 KB PDF) as presented by the Superintendent’s team. This minority report is also available for download (124 KB PDF) –Ed.

Introduction

The Superintendent’s Advisory Committee on Enrollment and Transfer (SACET) was asked to study and report on the “Three Big Ideas” for high school redesign. The three models were presented in broad strokes, with no analysis to support how the models would lower dropout rates, increase graduation or narrow the achievement gap.

The SACET report took note of these shortcomings, but failed to substantially analyze specific information that was given. The committee also failed to supplement given information with readily available data.

Specifically, SACET did not examine the three proposed high school models in light of:

- the clearly stated enrollment and transfer implications of the models,

- the number of campuses that would likely remain open with each model, and

- comparisons to existing high school models in the district and their successes and failures.

The committee also questioned the urgency of the process, which would seem to indicate a failure to appreciate how grossly inequitable our current system is. We don’t, in fact, currently have a “system” of high schools.

This lack of a central system (along with other factors, such as the school funding formula and allowance of neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers), has led to the statistical exclusion of poor and minority students from comprehensive secondary education in Portland Public Schools.

Therefore, it is of tantamount importance that we immediately begin implementing a system that eliminates race, income and home address as predictors of the kind of education a student receives in high school.

For the first time since massive revenue cuts in the 1990s began forcing decentralization of our school system, we are envisioning a single, district-wide model for all of our high schools. That is a remarkable and welcome step toward equity of educational opportunity in Portland Public Schools.

The focus of this minority report is on the three factors listed above: enrollment and transfer, number of campuses remaining, and comparisons to existing high schools.

Analysis of the Models

Special Focus Campuses

Large campuses (1,400-1,600 students) divided into 9th and 10th grade academies and special-focus academies for 11th and 12th grades. Students in 11th and 12th grades must choose a focus option.

Enrollment and transfer implications This model would more or less keep the existing transfer and enrollment model, and depend on an “if we build it, they will come” model to draw and retain enrollment in currently under-enrolled parts of the district by focusing new construction in these areas (per Sarah Singer).

School closure implications This model would support 6-7 high school campuses, leading to the closure of 3-4.

Comparison to existing schoolsThis model would draw on the “small schools” models that have been tried with varying degrees of success at Marshall and Roosevelt, and which have been rejected by the communities at Jefferson and Madison. It would also use the 9th and 10th grade academy model that has been successful at Cleveland.

Neighborhood High Schools and Flagship Magnets

Moderately-sized (1,100 students) comprehensive high schools in every neighborhood, with district-wide magnet options as alternatives to attending the assigned neighborhood school.

Enrollment and transfer implications This model would eliminate neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers, as well as the problems that go with them: self-segregation; unbalanced patterns of enrollment, funding and course offerings; and increased vehicle miles. School choice would be preserved in the form of magnet programs.

School closure implications As presented, this model would support 10 high school campuses, requiring none to be closed.

Comparison to existing schools This model most closely resembles the comprehensive high schools that are the most successful and are in the highest demand currently in Portland Public Schools.

Regional Flex

The closest thing to a “blow up the system” model. The district would be divided into an unspecified number of regions. Each region would have a similar network of large and small schools, with students filling out their schedules among the schools in their region.

Enrollment and transfer implications Transfer between regions would be eliminated, allowing sufficient enrollment to pay for balanced academic offerings.

School closure implications Most high school campuses as we know them would be closed or converted, in favor of a distributed campus model.

Comparison to existing schools This model would draw on both small schools and comprehensive schools currently existing in our district, but as a whole would be more similar to a community college model than any existing high school model in our district.

Recommendation

It is understood that these models represent extremes, and that the ultimate recommendation by the superintendent will likely contain elements of each.

That said, the Neighborhood High Schools model is the closest thing to a truly workable model. If used as the basis of the ultimate recommendation, that recommendation will stand the highest political likelihood of winning a critical mass of community support.

Specifically, the neighborhood model:

- is responsive to high demand for strong neighborhood schools;

- supports a broad-based, liberal arts education for all students, but does not preclude students from specializing;

- balances enrollment district-wide, providing equity of opportunity in a budget-neutral way;

- preserves school choice, but not in a way that harms neighborhood schools;

- reduces ethnic and socio-economic segregation by reducing self-segregation;

- takes a proven, popular model (comprehensive high schools) and replicates it district-wide, rather than destroying that model in favor of an experimental model (small schools) that has seen limited success in Portland (and significant failures);

- preserves the largest number of high school campuses;

- involves the smallest amount of change from the current system, causing minimal disruption in schools that are currently in high demand;

- is amenable to any kind of teaching and learning, including the 9th and 10th grade academies and small learning communities; and

- preserves room to grow as enrollment grows.

This system is very similar to the K-12 system in Beaverton, which has a very strong system of choice without neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers.

The transfer and enrollment aspect of this model is its most compelling feature.

We have learned definitively that when we allow the level of choice we currently have, patterns of self-segregation and “skimming” emerge. These effects are aggravated by the school funding formula and a decentralized system. Gross inequities in curriculum have become entrenched in our schools, predictable by race, income, and address. These factors have also led to a gross distortion in the geographic distribution of our educational investment.

Clearly, in the tension between neighborhood schools and choice, neighborhood schools have been on the losing end. A high school model that includes neighborhood-based enrollment, while preserving a robust system of magnet options, is a step toward rectifying this imbalance.

We’ve also learned (through transfer requests) that our comprehensive high schools are the most popular schools in the district.

As we have experimented over the years with non-comprehensive models for some of our high schools, the remaining comprehensive schools have been both academically successful and overwhelmingly popular. The small schools model, while it has much to recommend, has been implemented in a way that constrains students in narrow academic disciplines, flying in the face of the notion of a broad-based liberal arts education.

There is certainly nothing wrong with small learning communities, but a system that requires students to choose (and stick with) a specialty in 9th or 11th grade is unnecessarily constraining.

A comprehensive high school can contain any number of smaller communities, including 9th and 10th grade academies. Older students may be assigned to communities based on academic specialty, but that shouldn’t preclude them from taking classes outside of that specialty.

The Neighborhood High Schools model clearly does not do everything – our district will remain segregated by class and race. But it would move in the right direction by eliminating self-segregation and beginning to fully fund comprehensive secondary education in poor and minority neighborhoods.

The enrollment and transfer policy could be further tweaked to help reduce racial and socio-economic isolation, as well as to alleviate community concerns that the reduced transfers will lead to poor and minority students being “trapped” in sub-par schools.

To this end, neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers could be allowed, so long as they do not worsen socio-economic isolation. In other words, a student who qualifies for free or reduced lunch could be allowed to transfer to a non-Title I school, and a student who doesn’t qualify for free or reduced lunch could be able to transfer to a Title I school. This is a form of voluntary desegregation that is allowable under recent Supreme Court rulings, since it is not based on race.

Conclusion

All of these models show creative thinking, and, most importantly, a strategic vision to offer all students the same kinds of opportunities, regardless of their address, class, or race. The importance of this factor cannot be overstated.

While none of the models specifically addresses the teaching and learning or community-based supports that are necessary to close the achievement gap and increase graduation rates, they all are designed to close the opportunity gap.

But only the neighborhood model hits the right notes to make it politically feasible and educationally successful: strong, equitable, balanced, neighborhood-based, comprehensive schools, preserving and replicating our most popular, most successful existing high school model, and keeping the largest number of campuses open. The choice is clear.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

18 Comments

February 13, 2009

by Steve Rawley

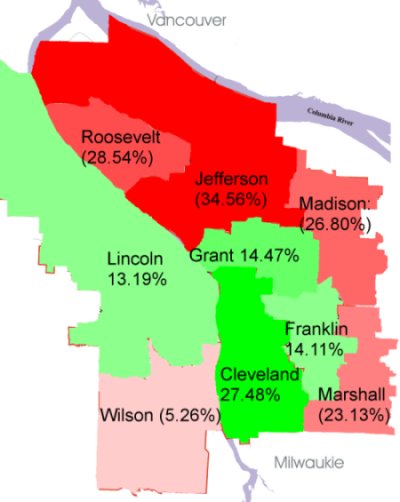

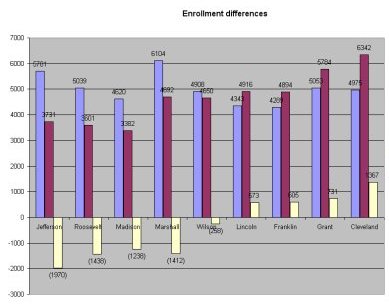

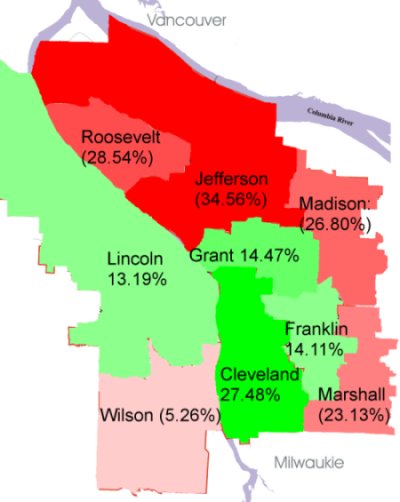

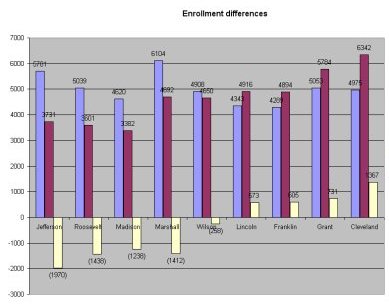

2008-2009 PPS student migration

Percentage of enrollment gained (or lost) due to student migration (compared to cluster population)

Student population vs. enrollment

Availability of comprehensive secondary schools correlated with race and poverty

| cluster |

# comp. high schools |

# comp. middle schools |

% non-white by residences |

% free/reduced meals by residence |

| Jefferson |

0 |

0 |

67.48% |

61.39% |

| Roosevelt |

0 |

1 |

67.6% |

72.30% |

| Madison |

0 |

0 |

61.95% |

61.77% |

| Marshall |

0 |

1 |

57.96% |

72.79% |

| Wilson |

1 |

2 |

24.57% |

20.80% |

| Lincoln |

1 |

1 |

21.60% |

9.30% |

| Franklin |

1 |

1 |

35.05% |

38.52% |

| Grant |

1 |

2 |

32.85% |

23.17% |

| Cleveland |

2 |

2 |

27.16% |

30.15% |

Note: teacher experience and student discipline rates also correlate highly to race and poverty; that is, average teacher experience is lower and discipline referral rates higher in schools serving high poverty, high minority populations. Data for the current school year are not yet available for these factors.

Data source: Portland Public Schools.

This report is available in PDF format (240KB).

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

15 Comments

November 14, 2008

by Steve Rawley

There is a school district, of similar size and demographics to Portland Public Schools (37,789 students, 42% minority, 33% free and reduced lunch, 16% ELL), with less funding per student than PPS, that manages to maintain strong and equitable neighborhood schools and a vibrant school choice program.

All of its neighborhood K-5 schools have music, P.E. and a library (staffed with a certified media specialist).

Options start in the middle grades (6-8), with every student assigned to a comprehensive middle school. Every neighborhood middle school offers world languages and elective options in the arts such as band or orchestra, choir and art. All middle schools also have after-school activities.

If a family is not happy with their comprehensive middle school assignment, they can choose from one of three K-8 schools, or one of several schools specializing in the arts, health and science, environmental science, an international school, or a school for highly gifted students.

As with the middle grades, every high school student is assigned to a comprehensive high school, each offering a broad and deep selection of advanced placement classes, world languages and electives, including fine arts (instrumental music, theatre, art, etc.), business, technology, etc., and each offering a wide variety of after-school programs.

For students looking for options not available in their assigned high school, choices include continuations of the middle grade arts, international, and health and science schools, as well a high school focused on science and technology and a “small school” focused on individualized instruction, independent learning, and real-world experience. They may also enroll in an International Baccalaureate program.

How do they do it?

- Their system is grounded in neighborhood-based attendance. Neighborhood schools are strong enough and offer enough of a comprehensive curriculum to be the first choice of the vast majority of families.

- Choice is limited to option schools; neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers are only allowed in exceptional circumstances. With schools sized according to attendance area, they are able to maintain funding and programming.

- Schools are considerably larger than schools in PPS (with K-5s around 600 students, middle schools 1000 and high schools 2000), with the trade-off of comprehensive curriculum in every neighborhood school.

And what’s the school district? Beaverton.

It is remarkable how well-planned, consistent, fair and equitable Beaverton is. They actually have a well-designed system of K-12 education, with a well-thought out curriculum guaranteed to every student in every neighborhood school that is as good or better than the best of the best in PPS.

Compare and contrast this to the shameful, utterly disorganized state of Portland Public Schools, where this kind of schooling is only available in the whitest, wealthiest neighborhoods.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

11 Comments

October 12, 2008

by Steve Rawley

How student transfers, “small schools,” and K8s steal opportunity from Portland’s least wealthy students, and how we can make it right

When speaking with district leaders about the glaring and shameful opportunity gap between the two halves of Portland Public Schools, it doesn’t take long before they start wringing their hands about enrollment.

“If only we could get enrollment up at Jefferson (or Madison, Marshall or Roosevelt),” they’ll tell you, “we could increase the offerings there.”

Or, as PPS K8 project manager Sara Allan put it in a recent comment on Rita Moore’s blog post about K8 “enrichment”: “All of our schools that are small … face a massive struggle to provide a robust program with our current resources.”

Not to pick on Sarah, but this attitude disclaims responsibility for the problem. After all, the “smallness” of schools in the PPS “red zone”* is by design, the direct result of three specific policies that are under total control of PPS policy makers:

- the break-up of comprehensive high schools into autonomous “small schools”

- the transition from comprehensive middle schools to K8s, and

- open transfer enrollment.

Smallness is not a problem in and of itself, but it is crippled by a school funding formula in which funding follows students, and there is little or no allowance for the type of school a student is attending (e.g. small vs. comprehensive or K8 vs. 6-8).

So when you’re dealing with a handicap you’ve created by design — smallness — it’s a little disingenuous to complain about its constraints. Instead, we need to eliminate the constraints — i.e. adjust the school funding formula — or redesign the handicap.

Adjusting the school funding formula to account for smallness would be ideal, if we had the funding to do it. Since we don’t, this would mean robbing Peter to pay Paul. That is, we would have to reduce funding at other schools to pay for smallness brought on by out-transfers, the K8 transition, or the small schools high school model. This obviously hasn’t happened, and it would be political suicide to suggest we start.

So barring a new source of funding to reduce the constraints of smallness, we need to redesign smallness.

The easiest case is the “small schools” design for high schools. Where students have been constrained to one of three “academies,” with varying degrees of autonomy, we simply allow students to cross-register for classes in other academies. Instead of academies, call them learning communities. Instantly, students at Madison, Marshall and Roosevelt have three times the curriculum to choose from. The best concepts of “small schools” — teachers as leaders and a communities of learning — are preserved.

For K8s, the problem is simply that we can never offer as much curriculum with 50-150 students in what is essentially an elementary school facility as we can offer at a middle school with 400-600 students. So we offer a choice: every middle grade student can choose between a comprehensive middle school or continuing in their neighborhood K8. Reopen (or rebuild) closed middle schools in the Jefferson and Madison clusters, and bolster those in the Roosevelt and Marshall clusters. Families in every cluster then have the choice between a richer curriculum of a middle school or the closer attention their children may receive with a smaller cohort in a K8. We all like choice, right?

Which brings us to the stickiest wicket of the smallness problem: open transfer enrollment, which conspires with K8s and “small schools” to drain nearly 6,000 students from the red zone annually (that’s 27% of students living in the red zone and 12% of all PPS students). We’re well-acquainted with the death spiral of out-transfers, program cuts, more out-transfers, and still more program cuts. It has reached the point that it doesn’t even matter why people first started leaving a school like Jefferson.

If you look at Jefferson now, compared to Grant, for example, It’s shocking what you see. Not counting dance classes, Jefferson offers 38 classes. Grant offers 152.

What kind of “choice” is that? (Disclaimer: both the Grant and Jefferson syllabi listings may be missing courses if teachers have not yet submitted their syllabi.)

Obviously, given funding constraints, we can’t afford to have a school with 600 students offer the same number of classes as one with 1,600, as district leaders will readily point out. What they’re not fond of talking about is the budget-neutral way of offering equity of opportunity in our high schools: balance enrollment.

All of our nine neighborhood high schools have enrollment area populations of 1,400-1,600. Jefferson and Marshall, two of our smallest high schools by enrollment, are the two largest attendance areas by residence, each with more than 1,600 PPS high school students.

With a four-year phase-in (keeping in mind that transfers into Lincoln, Grant and Cleveland have basically been shut-down for a couple years anyway), you start by making core freshman offerings the same at every neighborhood high school. Incoming freshman are assigned to their neighborhood school, and they don’t have to worry about it being a gutted shell. (Transfers for special focus options will still be available as they are now.) The following year, we add sophomore classes, and so on, and in four years every neighborhood high school has equity in core sequences of math, science, language arts, social studies, world languages and music, paid for without additional funding and without cutting significant programs at schools that are currently doing well.

Once we have this balance in place, both in terms of offerings and enrollment, we can talk about allowing neighborhood-to-neighborhood transfers again, but only as we can afford them. In other words, we will no longer allow a neighborhood program to be damaged by out-transfers.

It’s time for Portland Public Schools to stop blaming its opportunity gap on the smallness it has designed — by way of “small schools,” K8s, and open transfer enrollment — and it’s time for policy makers to stop transferring the costs of smallness to our poorest students in terms of dramatically unequal opportunities.

—

*I define the red zone as clusters with significant net enrollment losses due to student transfers: Jefferson (net loss of 1,949 students), Madison (1,067 students), Marshall (1,441 students) and Roosevelt (1,296 students). (2007-08 enrollment figures.) This represents, by conservative estimate, an annual loss of $34 million in state and local educational investment to the least-wealthy neighborhoods in Portland. “Small schools” were implemented exclusively in these four clusters, and the K8 transition, though district-wide, has disproportionately impacted the red zone. There are only two middle schools remaining in the red zone, one in the Roosevelt cluster and one in the Marshall cluster. By contrast, the Cleveland and Wilson clusters each have two middle schools; Franklin, Grant and Lincoln each have one.

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

15 Comments

July 1, 2008

by Steve Rawley

Sixty-one years after Mendez v. Westminster, 54 years after Brown v. Board of Education, 51 years after the Little Rock 9, 48 years after Ruby Bridges, 45 years after George Wallace caved to the national guard at the University of Alabama, 28 years after Ron Herndon stood on the school board desk and demanded equal opportunity for Portland’s black school children, and two years after city and county auditors demanded justification for effectively segregationist enrollment policies, Portland Public Schools have become more segregated than the neighborhoods they serve.

The school board refuses to answer the auditors, and shows no intention of changing the policies that have created the situation.

The segregation (or “racial isolation,” as the district calls it) would not be so objectionable, if it weren’t for the fact that schools in predominantly white, middle class neighborhoods have dramatically better offerings than the rest of Portland.

The desegregation plan hatched by Herndon’s Black United Front and pushed through by then-school board members Steve Buel, Herb Cawthorne and Wally Priestley in 1980 did away with forced busing of black children out of their neighborhoods, added staff to predominantly black schools, and created middle schools out of K-8 schools to better integrate students within their neighborhoods.

For several years, things clearly got better for non-white, non-middle class students in PPS. Then the nation-wide gang crisis hit Portland in 1986, with white supremacist, Asian and black gangs wreaking havoc and contributing to a wave of white flight from Portland’s black neighborhoods and schools. This was followed by the draconian budget cuts of Oregon’s Measure 5 in 1990, which ended the extra staffing brought by the 1980 plan.

Under inconsistent funding and unstable central leadership throughout the 1990s, central control over curricular offerings devolved to the schools, and the gravity of a self-reinforcing pattern of out-transfers and program cuts became virtually insurmountable.

The devolution of curriculum was formalized under the leadership of Vicki Phillips in the early 2000s. Her administration pushed market-based reforms and “school choice” as a salve for the “achievement gap,” and used corporate grants to extend reconfiguration of high schools in poor neighborhoods into “small schools” which severely limited educational opportunities available to Portland’s poorest high school students.

(Small school conversions were tentatively under way at Marshall and Roosevelt when Phillips took office, but didn’t become the de facto model for non-white, non-middle class schools until Phillips pushed it through at Jefferson, against community wishes, and finally at Madison, casting aside the designs of veteran educators who had initiated the concept.)

A bond measure whose revenue was intended to restore music education to the core curriculum was instead frittered away in the form of discretionary grants to schools. Principals in poorer neighborhoods continued to put teaching resources into literacy and numeracy at the expense of art and music, while schools in white, middle class neighborhoods continued to offer a broad range of educational opportunity.

The Phillips administration also began to dismantle middle schools in poor neighborhoods, including, notably, Harriet Tubman Middle School, which was created under the 1980 desegregation plan. This move back to the K-8 model added significantly to the resegregation of middle school students.

It also turns out that middle schoolers in K-8 schools, who are disproportionately non-white and poor, get fewer educational opportunities at greater cost to the district. Predominantly white, middle class neighborhoods have, by and large, been allowed to stick with the comprehensive middle school model, which allows them to offer a much broader range of electives, arts and core curriculum at no additional cost.

So in 28 years, we have moved from a reasonable semblance of equal opportunity, with schools’ demographics reflecting their neighborhoods’, to a demonstrably “separate and unequal” system, with schools more segregated than their neighborhoods.

Current policy makers like to blame Measure 5 and the federal No Child Left Behind Act for the wildly distorted educational opportunities in the district, and they generally refuse to examine district policy in the context of the advances in equity that were realized 28 years ago.

PPS has managed to maintain pretty good schools in white, middle class neighborhoods through years of stark budget cuts, but they have left poor and minority children fighting over crumbs in the rest of Portland. Even as the steady march of gentrification makes our neighborhoods more integrated, our schools are more segregated than they were in the early 1980s.

When today’s school board speaks of “school choice,” the “achievement gap” or “equity,” they appear to speak in a historical vacuum. I hope to remind everybody of the context of PPS’s policies, and the continuum of institutional racism they are a part of. These policies are indeed racist in effect, no matter how they are rationalized or how they were originally intended.

And no matter how much they complain that their hands are tied, or how much they claim to be making progress by “baby steps,” the school board has total control over district policy. They could start rectifying this immediately if they wanted to. Yes, it’s hard — ask Steve Buel or Herb Cawthorne about their late-night sessions trying to push the 1980 desegregation plan through — but it can be done.

I know there are school board members who care deeply about equal opportunity. They may even be in the majority, depending on who is appointed to replace Dan Ryan.

But nobody on today’s school board has demonstrated the political courage or vision necessary to stand up for all children in Portland Public Schools.

With baby steps, we will never get where we need to go. Bold, visionary action is required.

Edited January, 2016: For more background on Ron Herndon and the Black United Front, watch OPB’s Oregon Experience Episode “Portland Civil Rights: Lift Ev’ry Voice.”

Steve Rawley published PPS Equity from 2008 to 2010, when he moved his family out of the district.

34 Comments